Annmarie Lewis, Criminal Justice Programme Manager, gives an update of what’s coming up for the CJ programme and the T2A Transition into Adulthood campaign

If you follow Barrow Cadbury Trust’s socials and subscribe to our enews, you may have noticed a bit of a hiatus in criminal justice programme news and about what T2A is currently working on. There’s a good reason for this – I came into the post last November, excited at the prospect of getting my teeth into the work of the programme. In those seven months alone there have been significant events which have confirmed the need to stand back and review our direction and focus – and me being new-ish in the post is a good reason to do that.

Most of you already know what those events are so no need to list them here, but briefly the Sentencing Council’s new guidelines and the subsequent suspension of them, the publishing of two Sentencing Review reports, overcrowding in prisons and early release programmes, the shift toward policies which might be defined as ‘retrogressive’ and knee jerk, and an incline towards negative narratives, particularly around marginalised groups in the justice system – all good reasons to renew and refresh our programme.

Anyone working in and around the criminal justice system as I have for many years, will not be taken aback by the current lack of forward and creative thinking. However, it is not all doom and gloom. Gauke’s Sentencing Review had some positive elements – though the lack of reference to young adults and the work of T2A was disappointing (see our response to the review). And of course we are used to working in adversity – whoever’s in government and whoever is Justice or Prisons Minister. Over the last 20+ years of T2A, and more than 100 years of Barrow Cadbury Trust, this hasn’t stopped us from making and proposing changes and we are committed to carrying on in this vein.

Coming up …

So what’s coming up in the coming 12 months? Strategic communications have played an important part in our migrations programme, but now a group of CJ funders, including JABBS Foundation, Lankelly Chase, Pop Culture, Chanel Foundation, Henry Smith, Joseph Rowntree, Esme Fairbairn and others have banded together to work out how to counter harmful narratives for working with the public, media, and policy makers. The ‘two tier’ rhetoric has been unhelpful – and not just in the criminal justice sector but in other sectors as well.

Partnerships and changing narratives

We are strengthening our partnerships including the one with Corston Independent Funders Coalition, and the Harm to Healing partnership, so we can be more effective funders, reduce duplication, highlight critical gaps, and collaborate on counter narratives challenging toxic and harmful ones across criminal, racial and gender justice. There is no doubt this will be a challenge; research has found that increasingly people aren’t worried about misinformation or disinformation. AI is creating a whole other level of communicating that we need to get on top of if we’re not to get overwhelmed by negative content. The Edelman Trust Barometer 2025 has found the more something is ‘red-flagged’ the more some people will share it – whether it’s damaging, incorrect, or harmful. The media landscape is becoming more complex, more polarised, and influences from the US and other parts of the globe are making the job of changing negative narratives harder and harder.

Grassroots

But there is some amazing work being done at grassroots. Spark Inside held a round table to talk about taking forward six months of conversations with young men and colleagues from the prison, healthcare and voluntary sectors, building on the work of their Being Well, Being Equal campaign and report. This was a chance to bring together leading policymakers, practitioners and experts in the field of wellbeing, young adults and racial equity, talking about what health and justice colleagues can do to support and inform their work with young Black men.

Making the evidence base more accessible

We have more than 20 years of evidence around why we need a dedicated approach to young adults in the criminal justice system. Our plan is to synthesise that evidence base to distil best practices and create a blueprint for a transformed justice system for young adults. And that blueprint will include embedding individuals with lived and learned experience of the criminal justice system into the T2A ‘programme’, establishing a T2A advisory panel.

Finally, we will be ramping up our focus on advancing racial and gender justice within the criminal justice system, identifying and challenging systemic biases and inequalities. We will ensure that all campaign, advocacy and influencing work is underpinned by a strong commitment to reducing disparities and enhancing fairness.

Collaboration

At the end of this month we have our first workshop in a series of four. This first one will look at the current criminal justice ‘system’ and what we mean by that. To what extent is it a system, and which bits of it work? The second workshop will look at the system in more depth, the third will present our literature review, and the final one will look at narrative change. Our plan is for all four workshops to feed into a 2026 conference – the first significant T2A conference in 10 years. If you’d like to be kept informed about the workshops and any other activities, sign up to our enews on the T2A website, and follow us on LinkedIn and Bluesky.

I hope you will find everything that I’ve outlined resonates with your own ambitions and focus. Looking forward to working with you!

Annmarie Lewis, June 2025

Background

A new MoJ ‘process evaluation’ of Newham Y2A Probation Hub, a specialist youth to adulthood transitions service, which Barrow Cadbury Trust’s T2A (Transition to Adulthood Alliance) has supported for several years, has concluded that it is a successful model. The process evaluation took two years to look in detail at the implementation of this specialist young adult Hub in East London.

The model is based on T2A evidence of what works for young adults. Over the last 20 years, T2A has focused on how best justice services can support young adults to build positive lives away from crime. T2A’s core ask is for a distinct service that takes the best elements from youth justice services and develops them for young adult use. These services would be ‘young adult first,’ trauma-informed, strengths-based, and build strong pro-social identities.

The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), with support from the Ministry of Justice, London Probation Service and the Treasury’s Shared Outcomes fund, set up the Hub in March 2022 to respond to the specific needs of young adults on probation in Newham. It was purposefully and carefully designed to meet the specific needs of young adult, with input from young adults themselves.

The set up

A purpose-built space was developed so that young adults could be supported separately to older adults. Young adults were consulted during the design stage and all staff had specialist training in trauma-informed practice, neurodiversity, and developmental maturation. Staff worked with young adults on strengths-based and future-focused approaches. Flexibility around breach and enforcement was part of the ethos, and young adults’ successes were celebrated – a model adapted from youth justice services.

Alongside the mandatory service provided by probation, probation staff also supported young adults to access voluntary sector services such as mentoring and coaching, speech and language support, restorative justice, and housing support, along with education, training, and employment advice. Those young adults with mental health needs or who face extra neurodiversity challenges could access creative therapy.

Findings

Barrow Cadbury Trust’s ambition in supporting this project was that the Hub would be a template for the delivery of probation services to young adults across England and Wales.

The key finding of the process evaluation, was that the Hub had the potential to shape young adults’ maturational development and enable them to develop self-belief, build resilience, and regulate their behaviour.

Staff were positive about the impact of the Hub on young adults’ compliance and engagement, notably in the successful completion of sentences, as well as on young adults’ lives. The bedrock of the service is developing responsibility and forward planning skills that are all important for desistance. The evaluation found that staff were well-informed about the specific challenges facing young adults and supported them in responding to trauma in an informed, and person-centred way. Multiple services all on one site meant same day referrals were possible, and there were relatively short waiting times for first appointments, so that momentum built early on and made building relationships easier.

The evaluation highlighted the difficult life experiences that these young adults have faced in their short lives, including social and economic disadvantage, poverty and racial discrimination, reflecting the fact that Newham is the second most disadvantaged borough in London. Many had high levels of support needs because of their lack of maturity, their thinking, behaviour, attitudes and lifestyles. The evaluators recognised that these adversities and life changes take time to work through and overcome. Practitioners acknowledged this: “It takes time for young people who haven’t had the same benefits, the positive inputs, the positive attachments, the community. If they haven’t had that, they need time, and time isn’t two years … for long lasting change.”

How the Hub supported young adults

This model of delivering probation services to young adults, where the emphasis is on preparing them for a stable adulthood and independence, is significantly different to the offer available to older adults. Six core values – safety, trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment, and inclusivity are the essence of the Hub’s approach.

Although it is not the function of probation to turn children into adults, probation services can support the goal of reducing offending by assisting in the young person’s journey to independent adulthood. Young adults interviewed had a sense that maturity is something that develops and with the support of the Hub staff they felt empowered to put in place the building blocks to change their lifestyles.

It wasn’t just the young adults who recognised the benefits of the Hub. Staff welcomed the greater professional autonomy and flexibility they had as well as the advantages of holding pre-breach interviews before proceedings were necessary.

Young adults found the Hub a safe and welcoming area to engage, both with their probation officer and in therapeutic activities. This holistic approach made a crucial contribution to long-term positive outcomes. The wraparound support gives young adults the space to grow and learn about themselves.

The evaluation found that the Hub’s emphasises on cultural awareness and gender-specific services was appreciated by staff and young adults. This emphasis ensures that the diverse backgrounds and experiences of individuals are respected and valued, fostering a sense of belonging and understanding. The gender-specific approach recognises the unique needs and challenges faced by women, and how important tailored support is in a separate space, alongside other women’s services.

Outcomes/Experiences

One objective of the hub is to improve partnership working and information sharing between services so that young adults are less likely to fall through the net when children’s services support falls away at 18. The evaluation found that staff were able to develop strong, collaborative, trusted relationships with each other, with a shared purpose, and gain knowledge, formal and informally, from specialist professionals, a greater diversity of partners, as well as tapping into ongoing training and development. Probation officers benefitted from more time with young adults due to smaller caseloads.

The future

So far, more than 400 young adults have engaged with probation services in the Y2A Hub. The evaluation has demonstrated that success or failure of the service cannot be captured solely in reoffending data. T2A agrees with the evaluators that stage-specific services which help young people develop into mature adults are crucial. But we also recognise the importance of finding metrics for a young adult’s growth in their outlook, perceptions, maturity and self-identity.

The fact that staff and young adults interviewed were unanimously in favour of rolling out similar hubs in other parts of London and more widely is testament to the value of the model and the careful evidence-informed work that went into its planning. This is an innovation that the Government should be grasping with both hands, in line with its mission to “reduce the barriers to opportunity” and its ambition to tackle violence amongst young people. And the probation service deserves huge credit for putting evidence into practice and in so doing showing that the principles espoused by T2A have benefited young adults involved in the justice system.

This positive evaluation and the 20 years of T2A’s experience strongly underpin the need for young adults to receive specialist support, delivered in dedicated settings.

‘The starting point is not a goal but a collaboration’ – how Barrow Cadbury Trust has used systems change approaches to tackle complex issues in the justice system.

Young adulthood

How do you explain to people who don’t work in criminal justice about the distinct needs of young adults caught up in that system? Well, we held a mini 18th birthday party in our workshop room with balloons and birthday tunes! We then invited them to think back to when they turned 18 (or when someone they know turned 18).

Their reflections from this exercise were revealing and we identified three main themes:

| Feeling overwhelmed and uncertain

| ‘I didn’t have a bloody clue what I wanted to do!’ ‘It was very overwhelming at 18, I was trying to understand my place.’ ‘Overwhelm and excitement – yoyoing between those emotions.’ ‘I had undiagnosed mental health problems.’ |

| Testing boundaries

| ‘Testing boundaries and not always knowing where the boundary is and the repercussions until you’ve crossed it.’ ‘Experimenting with taking responsibility and consequences – it’s a never-ending journey.’ ‘I had a total lack of fear.’ ‘Learning from role models.’ |

| A social construct

| ‘Are you even really an adult at 18? In Sweden, you’re classed as an adult at 21. Adulthood is a social construct. It varies all over the world.’ ‘Are you really an adult at 18?’ ‘They said – but you’re an adult! I thought, oh great, but I still need help from adults!’ |

One attendee said afterward that they ‘particularly enjoyed the visualisation exercise - I mostly forgot that overwhelming jumble of thoughts and emotions around the age of 18.’

The group in question were attendees at the Systems Innovation Network Global Conference, mainly working in sectors such as health and sustainability, where systems thinking has taken root. Two of Justice Futures co-directors Gemma Buckland and Nina Champion, along with Laurie Hunte from the Transition to Adulthood Alliance at Barrow Cadbury Trust and Nadine Smith, a young justice advisor, were facilitating a workshop exploring how systems thinking can help improve outcomes for young adults in the justice system, and why a systems approach to funding is necessary to tackle complex issues and see transformational shifts.

Nadine explained the distinct needs of young adults in the criminal justice system including the fact that their brains are still developing and that the process of maturity doesn’t end at 18. She described the ‘cliff edge’ of services and support stopping and how young adults are often grouped with adults of all ages, whether in court, in custody or on probation, whereas we have a separate system for under-18s. She discussed her work with the Transition to Adulthood Alliance (T2A) and Leaders Unlocked, ensuring that young adults with lived experience are empowered to influence systems change by conducting research, designing services, and speaking to policymakers.

She set out that this is a complex issue as there is not one solution; it’s interconnected, multi-dimensional, and involves multiple and conflicting perspectives. In systems speak, this is known as a ‘wicked challenge’

The criminal justice eco-system

We then got attendees thinking about the different actors in the ecosystem that T2A works with and their multiple and conflicting perspectives. Using a Si Network Actor Mapping canvas, attendees were asked to imagine themselves as young adults, policymakers and practitioners to think about what values, power, mental models and incentives these actors have in the system when it comes to meeting young adults’ distinct needs.

When looking at power, attendees highlighted various types of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power dynamics including physical violence, money, the law, the power to ‘say no’, and even the power of an officer’s uniform. Incentives varied from hitting targets to ‘respect’, serving the community, to wanting a quick exit from the system. Mental models included ‘do the time, do the crime’, ‘prison works’, crime being caused by individual choice rather than societal failures and the ‘punishment v. rehabilitation’ dichotomy. Lastly, the values influencing actors in the ecosystem noted by participants were protection, risk reduction, efficiency, the rule of law, empathy, and suspicion.

The purpose of the exercise was to better understand what’s going on ‘under the surface’ with different actors in the system, so we can then work with the systemic patterns identified productively to affect change in the system.

As one workshop participant reflected ‘one of the most powerful exercises you can do is to step into other people’s shoes in the system.’ Another commented that ‘the ambiguities that arise are interesting.’ And one said it was ‘eye-opening. I could connect directly with some of the issues I’ve noticed in our neighbourhood. [It was] very effective in helping us look at these issues from different perspectives.’

These insights are what these systems tools are designed to bring out – helping people see differently, think differently and then do differently … our tagline at Justice Futures!

If we’d had more time, we would have discussed the insights the group had gained from examining the system from different actors’ perspectives and then used these to identify which leverage or intervention points would have the most long-lasting, positive impacts on the system. This is something that T2A, supported by the Barrow Cadbury Trust, has been navigating for the past two decades, as set out in a recent evaluation report by IVAR.

Changing the funding paradigm

We also used the actor mapping canvas to explore the values, power, incentives and mental models typically found in philanthropic funders, acknowledging that this is shifting (as we explore further below). For example, traditionally philanthropic funders might value learned expertise over lived expertise, favour funding short-term ‘sticking plaster’ solutions by looking for quick fixes, lack diversity, and might use models that promote competition rather than collaboration. They also often exercise some form of power, not only in the resources they hold, but in setting the criteria, timescales, decision-making and monitoring processes of their grants and project proposals.

Barrow Cadbury Trust is an unusual funder by taking a long-term, systemic approach to shifting paradigms. One example is their longstanding support of the Transition to Adulthood Alliance. IVAR recently evaluated this approach to systems change, and we highlighted some of the important key themes and learning from that report:

| Collaboration and relationship-building | ‘The starting point for T2A is not a goal but a collaboration.’

‘The best agendas for systems change work are built from diverse perspectives – no one knows “the right answer” |

| Power dynamics

| ‘Funders need to make a conscious and sustained effort to shift the paradigm in their interactions with others – from oversight to partnership.’

‘Systems change efforts have too often neglected the expertise of people with lived experience of these systems. Supporting their leadership and agency is increasingly recognised as crucial to achieving meaningful change.’ |

| Long-term commitment

| ‘A long-term view can absorb the ups and downs and the capacity to build relationships.’

‘We’re not governed by performance indicators – things taking a long time doesn’t deter us.’ |

| Working with emergence and unpredictability

| ‘Complexity theory captures the reality that over time you will encounter both the expected and unexpected.’

‘Working in and with complexity requires a different mindset and a different approach: dynamic, adaptive, emergent.’ |

IVAR’s findings mirror Catalyst 2030’s open letter for NGOs to sign, calling for funders to take a more systemic approach to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. One of these goals, SDG 16, relates to peaceful and inclusive societies and justice for all.

IVAR drew attention to Barrow Cadbury’s mindset shift, seeing themselves primarily as a systems change partner, rather than a funder. The report found the distinction between ‘being a player, rather than just an enabler’ has been deliberate and intentional, as Barrow Cadbury Trust are proud to both ‘drive and serve.’ This activism is done in collaboration with alliance members and with a vital awareness of the need to ‘out the power dynamic by relational means; listening carefully, responding to challenge, showing respect, being flexible, deferring to greater expertise and building partnershiprelationships not administrative ones.’

We also discussed a report and system map by New Philanthropy Capital showing that advocacy activities aimed at influencing political systems get less than 2% of all money going to criminal justice-focused NGOs and system coordination activities get less than 1%. We also highlighted the findings of two other reports (by Harm 2 Healing and Rosa) which show that grassroots, ‘by and for’ organisations promoting racial and gender justice often miss out on funding due to bureaucracy, a lack of unrestricted funding to support capacity building and the instability and uncertainty of short-term funding.

Laurie highlighted an example of partnership working between funders, where Barrow Cadbury convened a group of philanthropic funders to collaboratively help tackle racial disparities in the criminal justice system and address important issues of capacity building and leadership development for ‘by and for’ organisations.

We used the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops model to demonstrate the transition from the current dominant paradigm (in this case, funders as funders) to the new emergent paradigm (in this case, funders as systems change partners). We wanted to identify some of the ‘seeds of change’ happening globally and to start connecting and illuminating them.

Attendees gave examples of where they had started to see shifts from the current dominant paradigm of ‘funder’ towards ‘systems change partner’. Some interesting examples from around the world were shared, including:

- Children’s Investment Fund Foundation—a global funder which takes a systems change approach by investing in the long term, focusing on root causes, having a high appetite for risk, being flexible, and investing in building a thriving ecosystem and emerging leaders.

- Viable Cities – a challenge-driven, strategic innovation programme in Sweden where people submit ideas as individual organisations and then collaborate with other applicants to design projects to create climate-neutral cities by 2030.

- NCVO – a voluntary sector infrastructure body in the UK which is exploring the use of collaborative funding applications.

It was clear that attendees wanted to see more of these shifts in the future. As the IVAR report found, trusts and foundations are uniquely placed to support systems change as ‘they have the money, the time, and the patience. They can afford to take risks, to shift power, to disrupt, to play a leading role, like Barrow Cadbury Trust, or to be a patient cheerleader. All of these choices are in their gift.’

We hope the workshop gave a small taste of how systems approaches and systemic funding can help tackle complex issues, including in the criminal justice sector. As one attendee concluded, working in these ways helps bring people from ‘systems blindness to systems sight’.

Nina Champion, Gemma Buckland, Nadine Smith and Laurie Hunte

This blog post by Katy Swaine Williams was originally posted on the Prisoners’ Education Trust website

In conducting this study for Prisoners’ Education Trust (PET) on young women’s education in prison, I spoke to eight very different women, each with distinct, recent experiences of – and leading up to – imprisonment between the ages of 18 and 24. Five of the women were still in prison when we spoke.

It was striking to me how much importance all of the women placed on their education – past, present and future – and how determined many of them were, or had been, to access the best available opportunities in prison to help them make the most of the rest of their lives.

Most of the women were readily able to recall the areas of school life which they had enjoyed and achievements of which they felt proud, whether this was in sport, maths, cookery or psychology. This was accompanied for many by vivid recollections of negative experiences, including bullying and feeling unsupported by teachers, about which they clearly still felt the impact.

Some women described experiences of domestic abuse and coercive control which had had an impact on their experience of school and, in at least one case, continued to pose a risk to them while they were in custody.

For all the women in the study, it was clear that having access to purposeful activity in prison was fundamentally important. Whether through education, sport or employment, this was described as a source of satisfaction, distraction and relative normality, which helped them cope with incarceration.

Time spent inactive, on the wing, was something the women avoided wherever possible. For those who found themselves “stuck on the wing”, this appeared to lead to feelings of desperation and hopelessness.

Common barriers faced by young women

Recent research – including Gilly Sharpe’s longitudinal study Women, stigma and desistance from crime and the Young Women’s Justice project reports – has taught us about the ways in which young women who are often themselves the victims of serious crime or have experienced other forms of adversity (including early contact with the criminal justice system) can find themselves stigmatised, punished and ultimately abandoned by multiple state agencies, including the education system, social care system and criminal justice system. For many young women this builds upon similarly negative experiences during childhood.

This new study for PET echoes many of those findings and underlines how improving young women’s access to good quality education opportunities, both in prison and in the community, could help disrupt this negative narrative.

Like these eight individuals, all young women are different and no single approach to education in prison is going to suit every young woman. There is, however, a strong evidence base indicating common barriers faced by young women, which must form the foundation of future work to develop better educational opportunities for young women in prison.

We know that young women in prison are disproportionately likely to be suffering from mental health needs, often due to childhood trauma and abuse.

We know they are disproportionately likely to be at risk of ongoing gender-based abuse and exploitation.

We know that our understanding of girls’ experience of exclusion in education is under-developed.

We know from work by Milk Honey Bees and others that Black girls experience “adultification” and other harms in the education system.

We know that the over-representation of Black women and women from minority ethnic backgrounds throughout the criminal justice system is particularly acute for young women and even worse for girls. This points to experiences of discrimination which inevitably begin well before the prison gate and is a trend which we ignore at our peril.

There is also more work to be done – informed by insights from young women themselves – to fill gaps in our knowledge and develop solutions. For example, it was not possible in this study to explore the experiences of young migrant women, and this is one of a number of areas that need to be explored further.

Addressing system failures

The experiences of the eight young women in this study point to system failures which the Ministry of Justice’s planned Young Women’s Strategy – first promised in 2021 – must begin to address.

We have recommended that the strategy should include specific attention to improving access to good quality education and employment, informed through co-production with young women with relevant lived experience – including Black women, women from minority ethnic backgrounds and migrant young women – and women’s specialist services.

We have proposed that a more specialised structure should be put in place for young women in custody, modelled on provision for children with appropriate modifications, and filled with opportunities for meaningful and purposeful activity.

Several of the women described the lack of provision in prison to meet their mental health needs, including delays in mental health assessments, and subsequent delays in provision of support. Education helped some young women to cope with this, but the lack of mental health support was also felt as a barrier to engagement. We have highlighted the need for prompt assessments of mental health needs and of any ongoing risk of harm to young women from domestic abuse and other forms of violence against women and girls, as well as prompt provision of support, to aid their engagement in education.

It will be necessary to engage and retain highly skilled staff, with adequate resources, to ensure education opportunities are accessible to young women, that they are used as an opportunity to help improve mental wellbeing and confidence, and that they provide an effective stepping stone to future opportunities post-release – with appropriate ambition for young women’s futures. Having transitional support to continue with education and access employment post-release will also be key.

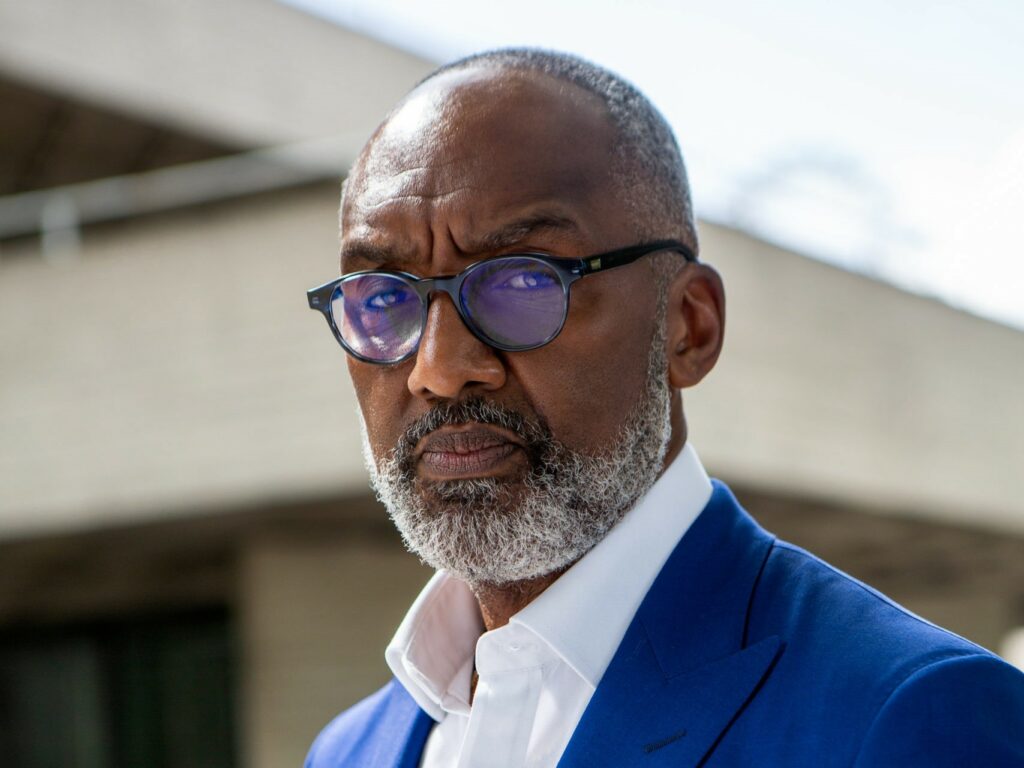

T2A Chair Leroy Logan MBE reflects on the findings of the Alliance for Youth Justice’s (AYJ) briefing paper on the transition from the youth to adult justice system – focusing on the experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people.

A spotlight on racial disparities

As the briefing suggests, young people who turn 18 while in contact with the justice system face a steep cliff edge. Studies show that this age is a crucial turning point where many young people begin to desist from crime with the right support and interventions. But rather than take advantage of this capacity for change, statutory services fall away. For Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people, the transition to the adult justice system can be even more challenging.

This latest briefing from AYJ has cast a harsh spotlight on the failings of our justice system to address the racial disparities that have blighted many young people’s lives. From an early age, many Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people find themselves associated with criminal stereotypes. Labelling young people in this way is incredibly damaging, eroding self-belief and making it harder to move towards a pro-social identity. Once Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic children enter the justice system, they are less likely to be diverted, more likely to receive harsher sentences, and more likely to be sent to custody, sentenced or on remand, compared to white children.

“Guilty before proven innocent… you kind of learn authority figures don’t actually care.” – (Young person)

This can create a huge gulf in understanding and trust between Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young adults and the professionals working in the system. Sadly, these findings confirm what many of us working in the sector already expected. That’s why I welcome AYJ drilling down into the causes of this crisis, and what needs to change to deliver better outcomes. Too often, we focus solely on what’s not working and forget that we must create a roadmap for the future we wish to see.

An over-stretched and under-resourced system

It’s clear that even with a diverse workforce, culturally competent training, and the best will in the world, the probation service is struggling to keep its head above water. A professional quoted in the briefing had this to say: “Record levels of staff sickness, extended sick leave, people fleeing the service in droves – that then exacerbates every other issue we have. We can’t be ambitious, we can’t be progressive, we can’t make many changes if you’re barely able to keep the regime running.” There are many admirable professionals working in the system who want to do better for young adults, but they don’t have the time, resources, or support to implement creative approaches. Without sufficient investment, the system can barely meet young adults’ basic needs – let alone support them to take steps towards a more positive future.

Collaboration with the VCSE sector

In this depressing climate, the work of voluntary and community organisations has become even more vital. Specialist Black and Ethnic Minority-led organisations have an intimate understanding of the communities Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people come from and how their experiences inform their behaviour and identity. As the research highlights, these grassroots organisations are well placed to provide nuanced support that recognises these young people’s overlapping needs – support that statutory services would struggle to provide.

These organisations are also more likely to have lived experience embedded in their staff and support services, meaning they can provide peer mentoring and positive role models – both of which are essential components in facilitating the shift towards a pro-social identity.

Ring-fenced funding to commission specialist organisations

I believe that we could take this further by developing a model where specialist Black and Minority-Ethnic led grassroots organisations are commissioned to operate services in their communities. Funding would be ring fenced for these local organisations who have the expertise to deliver the best outcomes. This model could be supported by local roundtables where information and knowledge are shared regularly so that young adults can access support from multiple agencies. Meeting in this way will also help criminal justice agencies better understand how these organisations are well placed to support young adults. Having buy in from all partners will be vital to the success of this model.

The Newham Transition to Adulthood Hub is a great example of how this approach can work in practice. They have a wide variety of services in one space, so staff can consult each other on individual cases and referrals to different services are much easier and more efficient. Regular spotlight sessions are held where different teams share their expertise and explain how their services can benefit young adults.

Grassroots organisations excluded from funding opportunities

Unfortunately, the AYJ’s report found that organisations with strong community links and knowledge are effectively excluded from funding opportunities. They lack the resources to compete with larger organisations who can meet the excessive commissioning processes and compliance requirements demanded by the Ministry of Justice and HMPPS. However, many of these larger organisations lack the knowledge and cultural competence to successfully deliver these services. Shockingly, they often sub-contract their services at a lower rate to the very grassroots organisations that have been denied a place at the table.

It is crucial that the Ministry of Justice and HMPPS immediately reform VCS funding allocation so that specialist Black and Minority-Ethnic led grassroots organisations can build the capacity of their services – ensuring every young person receives age-appropriate, trauma-informed, culturally competent services that reflect their entire lived experience.

A call for meaningful action on joint enterprise was made in the House of Lords some weeks ago, amid new evidence that current laws act in a discriminatory way and require a parliamentary response. Parliamentarians from all three main political parties raised questions following Lord Woodley asking the government:

“What steps they are taking to address concerns that joint enterprise case law operates in a harsh way against young black men.”

New data

The question followed new data on joint enterprise released by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) last month. The data is the first official research in over a decade about joint enterprise, the common term for the set of legal principles that allows more than one person to be prosecuted in relation to the same incident.

The CPS monitoring pilot, which tracked homicide and attempted homicide in six CPS areas, found Black young men aged 18-25 were the largest demographic prosecuted. Referring to the findings, Lord Woodley said:

“Black people are 16 times -I repeat, 16 times- more likely than white people to be prosecuted for homicide or attempted homicide under joint enterprise laws. It is absolutely shocking, as I am sure your Lordships all agree. Does the Minister therefore agree that this proves indisputably that joint enterprise is being used in a racist way by prosecutors, and basically as a dragnet to hoover up black urban youth?”

The CPS findings confirm those of previous studies. Last year research from the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, supported by the Barrow Cadbury Trust, found these trends have been consistent over at least the last decade.

Calls for the CPS to monitor joint enterprise prosecutions date back to a Justice Committee brief inquiry in 2014. However, the CPS only agreed to monitor joint enterprise prosecutions earlier this year following legal action by the campaign group JENGbA. Their case drew on several Barrow Cadbury Trust funded research publications, including Dangerous Associations and the Usual Suspects.

Next steps

In Thursday’s debate, Lord Marks of Henley on Thames questioned the use of racialised ‘gang’ strategies in the prosecution of groups. Several peers also raised concerns about the high threshold for appeal faced by those convicted under controversial laws.

Pressed about what the government is doing in response to the data, Lord Bellamy conceded:

“It is an essential part of our criminal law to have a joint enterprise doctrine. The question is: where are the edges to the doctrine?”

He set out plans for the CPS to extend its monitoring of joint enterprise across England and Wales and to review its guidance on ‘gangs’. Both are welcome. However, neither are new actions, having previously been agreed in the legal settlement reached with JENGbA.

Helen Mills, Head of Programmes at the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, who are currently supported by Barrow Cadbury Trust on this issue, said:

“We welcome the questions Lord Woodley and other peers are raising about young adults and joint enterprise. They demonstrate significant concerns, and questions about joint enterprise are a cross party issue. This requires the government to step up and commit to a comprehensive inquiry to address whether the current laws and practices underpinning them are fit for purpose, and what a fair, just approach to prosecuting groups looks like. They should not be to be dismissed by government as simply a legal matter to be left to the courts.”

“More than five years on since David Lammy’s review revealed the shocking extent of racial disproportionality in our criminal justice system, our report shows that many of the issues he identified remain stubbornly persistent.”

Of course, I welcome the transparency that this analysis brings. However, as someone who has worked tirelessly throughout my career to create a fairer criminal justice system, I am bitterly disappointed by the government’s lack of progress on its commitments.

In his 2018 Perrie Lecture, David Lammy said: “You cannot be in the criminal justice business and not be in the race business.”

And one cannot support children and young adults in the criminal justice system without being uncomfortably aware of the deep-seated racial disparities that exist. According to the Ministry of Justice’s statistics, over 40% of 18-24 year olds in custody are young Black and minority ethnic adults.

That’s why the work of T2A is hugely important. Together with T2A Alliance members, we’re doing all we can to ensure that every young adult in the criminal justice system gets the support they need, based on their ongoing maturity and not simply on their chronological age.

We often speak to practitioners across HMPPS who want to do more to support young Black and minority ethnic adults, so we must continue to create accessible resources and tools that enable them to do so.24 year olds in custody are young Black and minority ethnic adults.

Training materials should cover everything from understanding how to talk about race and increasing cultural awareness, to learning more about implicit bias and discrimination. Listening to Black and minority ethnic organisations and the young adult they support will ensure these materials are grounded in lived experience. Spark Inside’s recent #BeingWellBeingEqual report highlighted the importance of this approach, and how promoting young Black men’s wellbeing can help them unlock their full potential.

Learning how to support young adults to move from a pro-offending to pro-social identity will also be crucial. With a stronger insight into how identity and trauma inform behaviour, staff will be able to develop more positive relationships with the young Black and minority ethnic adults in their care.

I know that the scale of the challenges we face may feel insurmountable at times. Many people, myself included, are rightly disappointed that so little has changed since David Lammy’s landmark review five years ago.

But we must not let this deter us. We must harness this energy and relentlessly focus on the work ahead of us. And if you’re feeling a tad cynical, which is completely understandable, I invite you to delve into the power of optimism.

Want to learn more about how to support young adults in the justice system?

The changes have ranged from who may be referred to the Parole Board, to what professionals working for the Ministry of Justice can say to the Board in written and oral evidence. In the recent case of Bailey v SSJ the High Court said that one piece of guidance “may well have resulted in prisoners being released who would not otherwise have been released and in prisoners not being released who would otherwise have been released.” All the changes made by the current administration apply indiscriminately to anyone going through the process, regardless of age.

Young adults, currently defined by the Parole Board as 18-21-year-olds, only make up around 2% of its overall case load. But data revealed in a new T2A report on young adults and parole shows that there are some important differences in the characteristics of this cohort compared to older adults..

First, young adults are much more likely to appear before the Parole Board because they have been sent back to prison for alleged failures on supervision after automatic release from a standard sentence. The Board must then decide whether it’s safe to re-release them. Last year 97% of all initial ‘paper reviews’ by the Parole Board of young adults were because they had been recalled. Yet, across all age groups only 73% of cases concerned recalls.

A recent report by the Chief Inspector of Probation found that “most recalls to custody were caused by homelessness, a return to drug or alcohol misuse or a failure to ensure continuity of care pre and post release – not by re-offending.” Young adults can be particularly susceptible to be being recalled given that their developing maturity may make it harder to comply with licence conditions.

Second, when young adults are considered in more depth and have a chance to explain themselves to the Parole Board at an oral hearing, they are much more likely to be released than older applicants. In 2022, 59% of all young adults were released following an oral hearing whereas the overall release rate for all reviews was one in four.

The T2A AllianceIn the 18 years since its Independent Commission published Lost in Transition, Barrow Cadbury Trust has worked tirelessly to promote a more distinctive approach to young adults in the criminal justice system through T2A. This latest study looks at a relatively hidden corner of criminal justice that needs urgent attention. It’s very welcome that existing Parole Board guidance says 18–21-year-olds should be presumed suitable for an oral hearing if they aren’t released on the papers, but the study suggests more should be done to enable release at the initial paper stage or at least ensure oral hearings are convened as quickly as possible. Given the current pressures on prison places, it makes little sense to have young adults recalled to prison who are highly likely to be safe to release, sometimes staying there for a year or more. The Chair of the Sentencing Council has recently encouraged the use of suspended sentences where appropriate in light of the high prison population. The report also recommends that more should be done to ensure young adults, many of whom have high levels of need, can effectively participate in the parole process with the support of legal representation. This could also go some way to counter the systemic discrimination that persists for minoritised groups in prison and which has still not been addressed five years on from the Lammy review. It will also assist the very few young adult women that come before the Board but who require a specialised approach. Young adultsThe T2A report also argues that the Parole Board should treat those up to 25 as young adults, which would not only reflect the latest research on brain development but bring practice into line with many other agencies. For example, thanks in part to the influence of work by the Howard League and T2A, courts should now take account of the emotional and developmental age of an offender, and recognise that young people up to 25 are still developing neurologically. Greater application of this evidence-based approach by both the Parole Board and HMPPS will bring parole more into line with other parts of the system. The report makes a number of simple recommendations such as making sure the Board asks for the right kind of information before reaching a decision. When a young person has been in care, the Board should have information from social services. The Board should also interpret the test for release which it must apply in the light of what’s known about how young people mature, and how their risks of causing harm can be managed and reduced. The report recommends that the prison service gives young adults better access to the programmes, relationships and assistance which can help them prepare for success on release. ProbationProbation is also encouraged to provide more individualised support for young adults on licence in the community, but which does not overload them with complex requirements or impose conditions all but impossible to meet. The report finds mixed views about whether young adults are recalled too much but recommends this should be kept under close review, along with safeguards to prevent them going back to prison unnecessarily. Given the relatively small number of young adults going through the parole process, and the obvious benefits to reform, it is hoped that these recommendations will be both feasible and welcomed. |

When we see young adults in the criminal justice system solely as people to be punished, we deny them the opportunity to forge a better future. We rob them of their full potential. If we don’t rehabilitate young adults at this crucial juncture in their development, the desistance process becomes much more complex after the age of 25 due to the “scarring effect” of “new adversities which are emergent in adulthood” (University of Edinburgh Study March 2022).

Prisons should focus on the rehabilitation of every individual. Young adults who are given the chance to grow, develop and realise their potential during their time in prison are less likely to reoffend – and more likely to positively contribute to society. This is exemplified in a new report from Spark Inside. Its detailed paper Being Well, Being Equal contains a comprehensive list of recommendations on how we can prioritise the wellbeing of young men, and particularly young Black men in the criminal justice system. Spark Inside’s recommendations could not be more timely when we consider the scale of the challenges young adults face.

A 2021 thematic report from HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (HMIP) on the outcomes of young adults in custody stated: “if action is not taken, outcomes for this group and society will remain poor for the next decade and beyond.” The December 2022 HMIP thematic review into the experiences of adult black male prisoners and black prison staff found that lack of trust in prison staff was a significant barrier to asking for support.

“Prisoners generally had low expectations of the help that they might be given if they needed support; some gave examples of times when they or friends had sought support and not received it, and others did not feel that staff had the cultural sensitivity, expertise or experience to help them, and therefore did not want to ask for help.” (HMIP, 2022)

This places young Black men in the criminal justice system in an incredibly vulnerable position – one where they feel unable to seek help from the very people who have a duty of care to keep them safe.

The evidence is clear. We must act now. But where to start? Spark Inside believes we need to listen to the voices and experiences of young adults and the organisations that advocate on their behalf. Involving Black-led and Black specialist organisations in the development of wellbeing strategies will lead to greater engagement and trust on both sides – creating an approach to young Black men’s mental health and wellbeing that considers their distinct needs.

Empowering young adults to play a role in shaping policy and practice is also key. Being able to actively participate in matters that have a huge impact on their lives will boost their self-confidence, self-esteem, sense of agency, and wellbeing. Spark Inside have rightly identified that training and coaching will be vital to see through the report’s recommendations.

Many prison and probation officers want to do more to support young adults, but they don’t have the resources, time or support. HMPPS ringfencing time for staff to receive specialist training will help them understand how to effectively meet the needs of young adults – leading to more open and positive relationships. It will also help people working across the prison estate to explore and challenge discriminatory attitudes towards young adults, particularly young Black adults.

Right now, with organisations like Spark Inside working directly with young adults, we have a chance to create a criminal justice system that focuses on rehabilitation rather than punishment. A system where young adults can gain the skills and confidence they need to thrive. A system where every young adult can unlock their full potential. But we need to grab this chance with both hands if we are to ever make it a reality.

Last week’s publication of the long-awaited Delivery Plan for the 2018 Government Strategy on women’s offending has been met with a warm, but guarded, welcome by charities and others working to reduce the harm caused to women by the criminal justice system and prison. In January 2022 a National Audit Office report criticised the “disappointing” progress in implementing the strategy. This and the Public Accounts Committee report in April 2022 called for the Ministry of Justice to get a grip on delivery with a clear plan, funding and measures of progress.

Opportunity for change

The resulting Delivery Plan presents a real opportunity to create lasting change in this area. The three original Strategy aims – 1) Prevention and early intervention 2) Reducing the use of prison whilst increasing use of community sentences 3) Improving outcomes for women in custody – are now joined by a fourth: Improving outcomes for women on release. Ministry of Justice reporting on progress with the Plan will include remaining actions from both the Farmer Report (on the role of families) and the Concordat (to promote multi-agency action). The Delivery Plan includes much needed metrics about impact (rather than outputs) with baselines to measure progress, including on rates of arrest and prosecutions, numbers of prison sentences, reoffending and employment rates etc.

Omissions

There are some gaps in the Plan. It needs to explicitly include the Tackling Double Disadvantage: Ten-Point Action Plan published by an alliance of organisations led by Hibiscus, which has clear actions for change to address the double disadvantage experienced by Black, Asian and minoritised women. Unfortunately, the voices, strengths, and assets of women in the system don’t feature in the way they should. This has to be a golden thread throughout implementation, otherwise, initiatives like Problem Solving Courts and actions to support resettlement are likely to be undermined.

Keeping up the pressure

How can funders like Barrow Cadbury Trust and organisations that are campaigning and delivering services ensure this Plan delivers “deeds not words”? We know that shining a light on progress (and lack of it) is vital to influence those in power, to enable those involved to keep ‘chipping away’ at change, and to ensure accountability if that doesn’t happen. Organisations like Prison Reform Trust and Women in Prison have shown that forensic follow-up on commitments is vital and helps prevents actions from ‘falling through the cracks’. Sixteen years after Baroness Jean Corston’s clear blueprint for change, this has too often been the story for women in the criminal justice system.

Collaboration and Coalitions

Members of the new National Women’s Justice Coalition (NWJC), Corston Independent Funders Coalition (CIFC), Agenda, Clinks and others have demonstrated over the years how women’s specialist charities and independent funders are key partners in delivering impact, but they are too often overlooked by those in power. Officials working on probation service reform are already listening more closely to charities working on the ground. This new Plan is the opportunity to ensure these key players, and women themselves, are at the heart of a new system of justice. We know that “a goal without a plan is just a wish” and if this plan is funded and implemented properly, we could see a wish eventually become transformational systems change for women, families and communities.