This blog on racial justice in the VCS comes from Jeremy Crook OBE, Chief Executive of BTEG. It was planned as one of our 2020 centenary blogs. December’s Covid-related events pushed it into January – but it’s much too good to miss.

The Trust has had a strong involvement in racial justice issues over many decades. But this is a challenge to our own governance and management, and we are very aware that our board and senior management team are not sufficiently racially diverse. In a majority family governed foundation, racial diversity is an issue, and working with a small staff team we can only make new appointments when posts become vacant. The board has not been monochrome over the past five years and we are committed to increasing our Black and Minority Ethnic membership in the coming year. This has been written into our performance objectives as a Chair and a Chief Executive and we are currently working on it.

Erica Cadbury and Sara Llewellin

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Black Training and Enterprise Group (BTEG) was set up 30 years ago. We focus on helping children and young people succeed in education, employment and minimising their involvement in the criminal justice system. As one of the longest serving chief executives of a national charity, I want to reflect on how the conversation on race equality has changed in the voluntary and community sector (VCS).

I joined the VCS in the early 1980’s by volunteering for the Afro-Caribbean Youth Council, a charity in Walsall. The driver for its creation was social exclusion of black youth from mainstream organisations, school exclusions, lower educational attainment, youth unemployment, access to housing and police racism.

Race equality always felt like a peripheral issue in the VCS and was only supported by a handful of charitable trusts. The VCS was content to support race inequality initiatives if it did not reduce the resources available to the mainstream sector.

Last year an explosion of global anger was ignited by the killing of George Floyd in broad daylight on a public street by a group of police officers. Many parts of the world were awakened to how people of African origin are treated by the police, at work, on the streets, in the media, in the justice and political systems. The Black Lives Matter movement gave voice to more black people, many of whom have suffered in silence and/or been under-valued in the workplace for many years.

Reinvigorated scrutiny of the VCS highlighted that the presence of black and Asian people at senior levels in the VCS is extremely poor. There are some black and Asian individuals leading large charities and charitable trusts but, overall, their representation at senior levels is inadequate. According to ACEVO only 3% of charity CEOs were from black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds (2017).

It has also brought into focus what it means to be anti-racist in the VCS. Unacceptably, we still find race equality conversations in the VCS taking place without any black or Asian people present.

In the VCS the conversation shifted to discussions about the distribution of opportunities, the distribution of resources and the control of those resources. Whilst this is not the first time these issues had been considered it did feel for the first time that there was a cross-sector impetus, and more people are demanding more from their own leaders and organisations.

For much of the last thirty years [some] national VCS leaders engaged in discussions about racial inequalities but did not improve their own organisational performance. Equalities policies were adopted but there was no change in the ethnicity of those making decisions.

Young black, Asian and white people have demonstrated for change and are rightly rejecting tokenistic change in the VCS. It has been difficult, traumatic and uncomfortable, but it has provided a sense of hope that there will be change.

The issue of institutional racism has re-emerged with the usual denials that it exists in many large organisations. Structurally it would be easy to say that race equality never really featured in the core policy conversations within the VCS and, at best, it was a marginal issue often characterised with tokenistic gestures, e.g., the lone black or Asian individual employed to deliver the time limited ‘ethnic minority’ project.

In 2020 black and Asian colleagues in the VCS sector have demanded change. I think there are white leaders in the VCS that are prepared to listen and change their behaviour. They are prepared to use their influence and levers to tackle racial inequality. But there are leaders in large or influential organisations who are oblivious to the need for any change in the VCS. We all need to challenge and support these leaders to do better.

The conversation in some parts of the VCS has not changed – race equality is still not discussed. In other parts of the VCS what has changed is that the treatment of black people has been elevated up the management agenda. However, there is a risk that many white colleagues and leaders in the VCS view this as a moment and not the start of a transformation process.

Charitable trusts have also come under pressure to look at themselves and the equity of grant making decisions. Some have embraced this and have had a serious look at their organisation cultures, ethnic representation, and their relationship with black, Asian and minority ethnic organisations. Charitable trusts also have the lever of their grant making and must use this to drive change in the charities they support.

Government too has its procurement lever but has been reluctant to drive change. Large charities receive millions of pounds per year to provide public services and they should be held to account for bringing about change. For too long they have been dismissive of the need to reflect the ethnic diversity of their service users within their hierarchy. All too often black and Asian organisations have been excluded from the real decision making.

Today more importance is being placed on intersectional considerations – black and Asian individuals want to be respected and treated fairly for all their characteristics and not only in relation to ethnicity and colour. Black and Asian communities are demanding that they are not treated as a one-dimensional monolithic group.

We must be careful not to aid an inclination among leaders in the VCS to state the race equality box has been ticked now – “we’ve reviewed our policies so let’s move on now”.

Jeremy Crook OBE

In the spring we began a programme of publishing centenary blogs. We covered the Funder Commitment on Climate Change and the successful campaign for marriage equality in Ireland in February. Gender equality followed in March, and finally, in April, a blog on the anniversary of the Strangeways Riot – which led to the Woolf Report and its radical changes to the prison system. In the months that followed it seemed inappropriate to continue the focus on centenary blogs when all around us was so chaotic and with so much else that we needed to address.

When lockdown began in March trustees and senior staff put their heads together and resolved to carry on doing what we know from talking to our partners that we’re good at, rather than venturing into new territories or approaches, or throwing our doors wide open to meet huge emergency needs. As a small foundation we don’t have the resources to respond with financial support as others did.

But we immediately contacted all our partners to find out how they were faring, what their immediate needs were, and how they thought we could help them. We also wanted to reassure them that our support was secure for the long term and we wouldn’t be reassigning those funds for emergency support elsewhere. What remains important to the Trust is addressing structural inequalities through alignment with partners, advocacy, and influencing policy. None of that has changed, although the way we and our partners do that work has of course shifted and adapted.

Our programmes concentrate in the main on policy, campaigning and public opinion, and so we do not substantially fund frontline services. For this reason, we haven’t seen an enormous rise in new or emergency applications, nor have we thankfully experienced a drop in our endowment income – though this may of course change depending on numerous factors including the Brexit transitional process and economic downturn.

Like the majority of the social justice sector, we have all moved to home working and online trustee meetings, and the events held in our meeting rooms – part of our offer as a trust with meeting rooms in central London – have all moved on line. Using Zoom and Teams is now almost second nature but that is of course challenging for our relational model and we would all much prefer to meet in person and will hopefully return to that in the coming months.

In October we delivered £5m of National Lottery Community Fund (NLCF) emergency funding to organisations working with refugees, migrants and asylum seekers whose work had been affected by COVID-19. Nearly 200 organisations across England were given emergency grants up to £50k to use before April 2021. These were mainly service providing bodies, which are not our usual partners. Their work spanned grassroots community groups in Leicester helping abused and abandoned women with no migration status, to a London organisation providing bicycles to refugees and asylum seekers, run on a shoe string primarily by volunteers.

So, what have we learned from these past months? That the values we share with our partners are constant, but that we cannot be complacent about progress around inequality. Economic, gender, and race inequalities are not going away. On a positive note – public and political awareness about those issues and how they might be addressed and tackled has undoubtedly increased. The will to challenge institutional and structural racism is gaining ground and we hope to see that momentum translated into concrete changes. The ‘hostile environment’ is in lots of ways more hostile, but the strength of resistance challenging some of the hatred is palpable, however it manifests itself.

Examining our own house has been part of that process; in July I wrote a blog about the origins of our endowment, scrutinising the early commercial activities of Cadburys in relation to the labour which produced cocoa and sugar. You can read about what we found out here.

The Kruger report on civil society could be a useful tool to address some of the fall-out from the pandemic, though many of the ideas contained in it are reworked ones, and we are conscious that the government might be hoping the foundation sector will make up for the civil society funding gap which is inevitably approaching.

The sector is jittery and understandably so. Who knows how the next twelve months will pan out? For now our sights must be set on the nearer term recovery period rather than the next 100 years I alluded to in the January blog. Yet the climate crisis must remain front of mind as we cannot afford to lose any momentum on that. As the year ends, we are all utterly convinced that the need for a strong civil society is greater than ever.

In this year of unprecedented challenges for charities, we asked two of our trustees, Esther McConnell and Cathy Pharoah, to tell us about their experiences of being trustees of Barrow Cadbury Trust during the pandemic, what’s made a difference, what was difficult, and what might be round the corner.

Esther McConnell

Esther is the great great granddaughter of Barrow and Geraldine Cadbury. Esther became a Trustee in 2016. She currently works at the East European Resource Centre as the Deputy CEO. Previously, she worked at the Anti-Trafficking and Labour Exploitation Unit (ATLEU) and volunteered with Stop the Traffik. She studied Global Migration at UCL with a focus on community responses to migration and change.

“I don’t believe our risk register or strategy embraced the possibility of a pandemic or a national lockdown, though we had included the fallout by other means. Being a Trustee over the past eight or so months has meant grappling with this fast-changing and ever-complicating landscape – a landscape which has affected our charity, our people, and our partners.

Working with a grant-making charity often gives you a marvellous overview of the work and profile of a sector. From this viewpoint – it has been clear that COVID-19, the lockdown, and the associated economic fallout, have exacerbated existing inequalities and created new ones. Across our programmes there has been a whole lot of hardship and, at times, this has felt overwhelming. But there has also been a good amount of hope. Hope sprung, primarily, from the hard work and dynamism of our partners in all their different guises, and their staff.

But what of the finer details of governance operations? We have adapted ourselves to work remotely – with a simplified meeting structure and regular updates. We have missed speaking in person and sharing thoughts in that easy way we took for granted. But our staff have supported us to recreate a sharing environment by enabling small discussion groups within our agenda.

It has certainly been a very strange and disrupted year – but the consistency and steadfastness of BCT staff and fellow Trustees has meant that being a trustee has felt like a calm and steady ship in the storm”.

Cathy Pharoah

Cathy has been a non-family trustee since 2015. She is Visiting Professor of Charity Funding and co-director of the Centre for Charitable Giving and Philanthropy at Cass Business School. She is an expert on voluntary sector funding, specialising in research on philanthropy. She is a founder of Voluntary Sector Review, and presents widely on giving and philanthropy.

“The pandemic has brought challenge, change, privilege and opportunity to trusteeship. In a future of continuing uncertainty, it will continue to do so. Looking back to the anxieties of March the Trust might breathe a sigh of relief. Operations have been moved successfully to online and home working, a substantial programme of emergency and other grant-making has been delivered in a timely way, finances are still afloat, thankfully few staff and trustees have suffered from COVID19 infection, and Zoomed Board meetings have been efficient. And Board and staff are all still allies and friends.

However, none of the effectiveness in responding to the impact of the pandemic can be taken for granted. In the case of the Trust, it has been – and will continue to be – underpinned by the principles and ‘capital’ of good charity governance already in place. This includes high standards of financial and risk monitoring and oversight, clarity and unity around the charity’s mission and purposes, efficient managerial processes, regular detailed Board reporting and an organisational culture of learning. We have been able to draw on a well-oiled machine to develop rapid-fire, flexible approaches to the fast-changing landscape of grantee and beneficiary need. CEO and Chair leadership in steering the organisation through change, and supporting staff through the personal and professional challenges of the pandemic, have been vital. Trustees have had a key role in recognising the need to work differently, and providing fit-for-purpose oversight to enable staff to get on with the job in a timely way.

Most importantly, however, and critical in holding all the initiatives together, are the strong relationships of trust between staff and board members. From the perspective of a Trustee, these build up over time, through face to face engagements in Trustee meetings, events and joint project visits, not to mention invaluable, informal opportunities to get to know staff and other Trustees better at social occasions. We have lost these to the pandemic, and they are sadly missed. In the process, however, it is important also to recognise that trustee boards and staff have been sharing new experiences and partnerships together around fighting the impact of the pandemic and responding to calls for greater equality and diversity in the sector. These are providing the new platforms on which to build future governance, and more effective programmes for social change.

http://www.barrowcadbury.org.uk

We recently hosted a conversation for small charities with those who fund and support them, to explore their social change role over the next 12-18 months. This was partly to build on our recent publication of Small charities and social change, a study which describes the approaches of 11 small charities to advocacy; and partly because through our work in response to Covid-19, we’re hearing a lot about the need to strengthen the sector’s collective voice: ‘We have to have some real conversations. We’re lots of voices, collective voices, but we’re being drowned out with all the noise’.

The pandemic has presented many and varied challenges for small charities – and uncertainty is now part of the new normal. Alongside this, we have all been affected by the events that followed the killing of George Floyd – the protests, the debates, the anger, the pain, the calls to action. Profound questions are being asked about diversity, equality and inclusion – these need to be front of mind as we turn our attention to the process of recovery and renewal out of the crisis that we have been living through.

We were privileged to hear from four people with different experiences of social change: Raheel Mohammad, Director of Maslaha; Christopher Stacey, Co-Director of Unlock; Debbie Pippard, Director of Programmes at Barrow Cadbury Trust; and George Barrow, Civil Servant at The Ministry of Justice.

Seven things stood out from their reflections and the discussions that followed:

- ‘Covid-19 has pulled back the curtain and demonstrated the number of people that have been marginalised’ by previously unfair and closed decision-making processes. Small and medium charities undertaking social change work have to look at ways in which they can link up with other groups who are led by and/or represent individuals and groups whose voices and experiences are going unheard.

- ‘Majority white-led organisations do not have the specialist knowledge or expertise to understand how certain social issues affect communities of colour.’ Work to unpack and respond to the experiences of communities of colour must be led by or run in partnership with them so that it ‘registers emotion, vulnerability, heritage, culture and religion’. If this social change work is being carried out ‘through partnerships between black and brown-led and white-led and organisations’, it is most effective when based around something tangible: ‘it’s in the action that you open up new parameters and new horizons’.

- Ensure that you are actively and demonstratively accountable to the individuals, groups and communities you are advocating on behalf of. We must avoid being the creators or perpetuators of ‘artificial examples of good practice’, only putting forward solutions for policy and practice that are based on the genuine experience and voice of those you represent Always ask yourself: ‘Do you know what good looks like?’ for a particular group or community.

- Collaboration is essential, particularly between large and small charities. Larger charities are often more likely to have a seat at the table and have their voices heard, and they have the time and capacity to engage in decision making processes. But small charities tend to have the proximity to lived experience and in-depth knowledge of how policy and practice plays out on the ground.

- We must continue to work both inside and outside of the system. For example, building relationships with local and national government, but also being willing to mobilise and challenge where necessary. Recognise that it’s about understanding what is the most appropriate and effective strategy for the change you are seeking to influence at a given point in time.

- When attempting to influence central government policy or legislation, there are three things it is useful to keep in mind. First, develop personal relationships with key civil servants, or work in partnership with an organisation who can build or has these relationships. Second, work together in loose networks: ‘If you’re all on the same page we do get the message’. Third, understand that government moves slowly, so being able to commit and be in it for the long term is important. Small charities also have a very important role to play in being able to bring the ‘corporate memory’ on certain social policy issues and previously tried and tested solutions.

- More funders need to commit to funding social change work and understand what it takes to fund this kind of work. Be willing to fund over an extended period of time, stick with social change processes for the long term, and allow those doing social change work the freedom and opportunism to act in a responsive and adaptive way. More work may need to be done with trustees of trusts and foundations to help them to understand the importance of investing in social change work alongside service delivery.

You can read more about how and why small charities are challenging, shaping and changing policy, practice and attitudes here.

There comes a point in any crisis where critics on the side-line weigh in to point out all the things that are being done wrong.

To those in the eye of the storm, this can seem like an unnecessary distraction. But I do not think we should wait until the end of the pandemic before seeking constructive feedback, learning from our mistakes or altering our behaviour. It is very possible that our ‘new normal’ will be years of swinging between socially distanced public activity and lockdown. We all need to accept and respond to feedback while the work of responding to the pandemic continues.

But if we are to reflect on where civil society has done well and where it hasn’t, let’s not start by rehashing stale conversations about how ‘professional’ the charity sector is and whether we need to be more ‘business like’. Especially when being business-like hasn’t made the lives of businesses any easier in the last two months.

Instead the conversation should take as a starting point the core purpose of civil society: public benefit delivered for public good, not private gain. Throughout this crisis I have seen the true value of civil society in the volunteers delivering food to people unable to get to the supermarket, in the digitisation of befriending services to support lonely people, in the hospice workers and domestic abuse support staff going to work, risking their health so others can be safe, receive love and feel dignity.

Many civil society staff who have been furloughed have been keen to volunteer their expertise to other not for profit organisations. The generosity I have seen from colleagues across the sector, whether furloughed or not, volunteers or paid staff has continually and repeatedly inspired me.

Lockdown has also thrown a light on the things we value most, things that are too often dismissed as luxuries but are instead the mark of a well, healthy, happy society. Theatres, dance, access to green spaces, museums, community choirs, the local Scout, Woodcraft folk or Girlguiding troop, are all part of civil society. Civil society is already valued, it’s just that most people have no idea what ‘civil society’ means.

Our sector does not need to ape business or the public sector because we are not business or the public sector. In the past some of us umbrella and membership bodies whose role is to champion our distinct identity have been too reluctant to do so because of concern about the complexity of the sector, or fear of being seen as too ‘argumentative’, ‘unreasonable’ or ‘demanding’ by politicians. These are terms that are most often used to put people in their place, they are used by people in positions of power to remind those with less power to be grateful for what they are given, even when it isn’t what they need. All three terms are also highly gendered, classed and racialised.

The lack of knowledge and understanding about the role of civil society in central government has been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic. But we cannot expect politicians to understand the distinct nature of civil society if we do not shout about it. Similarly, we cannot complain that government expects solutions for businesses to fit charities if we are always talking publicly about trying to be more ‘business-like.’

By centring people and the environment in discussions about how the sector can improve we will build back better.

Some, but by no means all, of the questions I think are important for the sector to be reflecting and acting on now are:

- Who is at highest risk of experiencing harm and are civil society organisations reaching them? If not, why not?

- Who are the voices with access to power and are they representative of the people we serve?

- Is funding distributed by civil society being distributed equitably?

- Why doesn’t government understand civil society and how can we change that?

- How do we build on the strengths of the sector’s response to Covid-19 and learn from our failures?

It is also important to remember that many of the problems we are lamenting now existed before Covid-19. Civil society has seen its political influence gradually decrease for at least 10 years. Ways of working that were effective in the past will not work now. Part of being a good leader is a commitment to continuous learning.

So come and talk to us about how we build on the amazing strengths of the sector and address the weaknesses and the challenges. Wouldn’t it be something if in the future the government pointed at the voluntary sector and told businesses they need to be more like us?

In 2015, Ireland became the first country in the world to bring in same-sex marriage by a popular vote. A referendum where 62.07% of the electorate voted in favour of the amendment to extend civil marriage to same sex couples. This achievement built on years of activism which had succeeded in persuading the political system of the need to change our constitution and why the question should be put to the Irish people. We learnt many things from the campaign and here are some of my take-aways.

Communicate across difference – we learnt that we had to answer the questions in the minds of the voters. We had to listen to what those concerns were and then answer them in a language that appealed to each particular audience. We learnt that people need to see the relevance of the issue within the context of their own experience, the need to connect the campaign goal to the lives of ordinary citizens. The job of the campaign was how to link the struggle with the concerns of regular Irish people. We took on a divisive issue, a minority issue, and made it everyone’s business – your child, your cousin, your friend and your colleague. The campaign gave a glimpse of the kind of nation we could have, connecting with that basic human desire to achieve one’s better self.

Understand how attitudes are shaped and who we had to target and how. Our communications strategies were grounded on solid research that reflected the concerns, values and priorities of those we were trying to influence, especially the middle ground, undecided voter. The research was crucial in shaping the campaign’s message, tone and shape, to appeal to these voters.

Story telling was at the core – the campaign put personal stories at its heart. Exit polls showed the individual stories of those excluded from marriage equality played a huge factor in many people voting in favour. In this age of digital democracy, we learnt that large numbers of facts can be overwhelming. With so much so-called “truth,” the influencing value of personal stories was key to cutting through the noise and distraction.

Messengers were picked for their ability to talk to the undecided. These were complemented with surprising messengers – those who people didn’t expect to hear – and they influenced and connected with the middle ground. We found “unlikely” messengers worked well. We put a spotlight on the voices of “permission givers” like athletes, celebrities, faith leaders, the conservative parent of a gay son or lesbian daughter, and other role models, including the a former President of Ireland as a mother of a gay son.

We learnt to use our feet – the issue was forced onto the political agenda by thousands of activists up and down the country. These activists ran stalls, marched, organised, leafletted, canvassed, shared their stories and made so much noise they could be ignored no longer. It was these individuals that built the power for the referendum result.

We learnt that smart social media mattered – a cutting-edge social media strategy and smart use of analytics also ensured our campaigns had advantage. We channelled a nationwide army of voluntary effort by implementing a technology-assisted and monitored canvassing operation. Crowd-funding paid for our work. Social media gave us opportunities to tell personal stories, promote messages, and communicate with our supporters. The strategy also allowed individuals to be involved at their own pace.

In conclusion: we can never take these wins for granted and there is of course so much work still to be done. But we have lived through great social justice change in recent years, which is certainly cause for celebration. And 20 years ago it would not have seemed conceivable that so many countries would embrace such change.

Denise Charlton (http://denisecharltonassociates.ie) is an activist and consultant working in the area of Social Change and was co-founder of Marriage Equality.

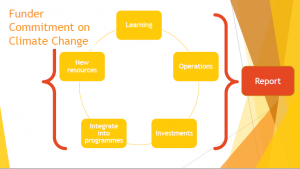

I’ve been talking with people about climate change for more than thirty years. Recently, one question has started to dominate all others: “what is it that I need to do?” We know climate change is happening, we know it’s serious, and we know we all have a responsibility – so what is it that I need to do? The Funder Commitment on Climate Change arose out of several charitable funders, including the Barrow Cadbury Trust, seeking an answer to that question.

In June 2019, at a gathering of foundation leaders, we heard persuasive evidence not only about the threat from rapid climate change, but also of the opportunities and costs of the necessary transition to a low carbon economy. For over a century, our economy and society has been shaped by the use of fossil fuels for electricity, heating and transport. Ending fossil fuel use therefore involves economic and social transformation. Similarly, moving from today’s agriculture to a more sustainable, mainly plant-based food system will also be a huge change.

In the coffee break, several of us got talking about “what it is we need to do” and the idea of a climate pledge or manifesto for funders was born. I offered to start the ball rolling, and was inspired by the amount of energy and interest it attracted.

Conversations continued over the summer. An early realisation was that the pledge had to be inclusive, and relevant to all foundations, whatever their size, governance or charitable mission. At the same time, it was vital to get beyond vague intentions, and several of the founding signatories rightly pushed for high ambition. We also agreed that the Funder Commitment needed to be holistic, recognising all aspects of our work – programmes, investments and operations – will need to change.

The language evolved through discussion and consultation. Initially known as a ‘manifesto’, we eventually settled on the term ‘Commitment’ as having the right connotations. We sought language that would speak to diverse audiences, mindful of the need to build a broad movement. The final text recognises opportunities, such as new industries and jobs, for example.

The Association of Charitable Foundations generously offered space at their annual conference in November to launch the Funder Commitment. This gave us both a platform and a deadline! The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation provided some seed funding, and Comic Relief supported the creation of a website. The final text, founding signatories and communications came together, all just in time.

On 6 November 2019, the Funder Commitment on Climate Change was launched in a packed room of foundation staff and trustees, with many more turned away at the door through lack of space. By the end of the day, inquiries were coming in from other foundations wishing to add their name. At the time of writing, we have topped thirty signatories, with Comic Relief the latest to join.

So, what have we all pledged to do, and why?

Addressing climate change needs large scale, urgent action. Money is needed for activism, for advocacy, for education, for business development, for practical action, and to support local communities through transition. Some foundations can provide grants, while others can give staff time or other in-kind support. So one element of the Funder Commitment is to commit resources. The slide below illustrates the way it works.

The causes and solutions of climate change interact with many other fields of civil society activity, ranging from housing to the arts, and from scientific research to social change. Foundations have an opportunity to build on their existing expertise and networks, to make productive links across different fields, and to foster positive action on climate in their own priority areas. Another part of the Funder Commitment is about this integration.

Next we come to foundation investments. Climate change is recognised as a risk to investments by the World Bank and Bank of England, amongst others. It is basic good stewardship to recognise and address this risk, and this is what the Funder Commitment requires. There are also many opportunities for foundations to take a more active leadership stance on responsible investment.

While for most foundations, our direct carbon footprint will be small relative to the impact we can have through our grants and investment choices, it is still important and empowering to get our own house in order – to show leadership, to engage stakeholders, and to manage reputational risks. So the Funder Commitment also covers the climate change impact of our own operations.

Every funder, and indeed every NGO, public body and commercial company, will be at a different stage in tackling climate change. This is an ongoing generational transformation, not a one-off task. For this reason, the Funder Commitment opens with a commitment to learning, and closes with a commitment to reporting on progress. What is it that you need to do?

Nick Perks

Find the full text of the Funder Commitment on Climate Change and list of current signatories here.

Nick Perks is a freelance charity and philanthropy consultant.

http://www.nickperks.org.uk/ @Nick_Perks_

In the last year as a board we have also been reflecting on our responsibilities as trustees of a family philanthropic endowment. We have questioned how we exercise our mandate and fulfil our role in the public domain when our endowment is derived from private wealth and as charity trustees, we are unelected.

We are still governed by a largely family board, descendants of the founders, Barrow and Geraldine Southall Cadbury, but are supported by non-family trustees. We recognise that board membership is both a privilege and a service and have taken steps to minimise the impact of that privilege.

Firstly, we recognise that this is not primarily ‘our’ money. It is held in trust for the public benefit and we must approach how we use it with care and humility, consulting and learning from our stakeholders and partners every inch of the way.

Secondly, the staff and trustee board endeavour to minimise the negative power imbalance in our relationships with all of our partners. We hope, as our stakeholders and partners, you’ll let us know when we fall short.

Thirdly we are committed to enhancing our skills as trustees so that our decision making is informed and responsible. Our non-family trustees augment our knowledge base and our perspectives. We also now ask family members who want to join the board to gain experience by serving a governance apprenticeship in a front-line charity.

Most importantly though, we consider ourselves to be an integral part of civil society. We believe we add value as actors, not just as observers or supporters, but in our own right, as all citizens are entitled to.

Over the past few months, as we prepared for the centenary, we reflected with great care on our long term goals and as trustees took the decision to protect the long term future of the endowment. In order to do this, we will have to reduce our spending from our capital to ensure that we have an adequate income in the future. We will do this gradually over our next five year strategic period. We have started to deliver several programmes now for other funding bodies, and we hope to develop this approach further.

As we embark on a new decade, we’ve also been impacted afresh by the surge of younger people renaming the climate crisis as an emergency. The Quaker activist John Woolman wrote presciently in the 18th century “the produce of the earth is a gift from our gracious creator to the inhabitants and to impoverish the earth now to support outward greatness appears to be an injury to the succeeding age”. In this spirit, last year we became founding signatories to the Funder Commitment on Climate Change and will be working over the coming months to translate that commitment to more action.

And in the midst of political turbulence and social division, I would like to draw your attention to the Decade of Reconnection, orchestrated by a number of our partners and others. Launching officially in the Spring, its purpose is to make deliberate efforts – all of us – to reach out respectfully to those who do not share our views. Let us reach out more and listen harder in the interests of a better future.

This blog is the first in a year-long series, drawing on ambitious and clear-sighted thinking and activities from a broad range of our partners, stakeholders and grantees – past and present. We are also delighted to launch our new animation ‘hot off the press’ which we hope captures how we arrived at this place, and very importantly where we’d like to be in another hundred years.

Erica Cadbury

Chair, Barrow Cadbury Trust

“They should have dealt with things properly. They should have listened to what I had said…I wouldn’t have gone through the things that I went through.” – Sheena

Girls and young women facing the greatest forms of inequality and disadvantage are frequently marginalised, ignored and misunderstood. Girls facing a combination of problems – like abuse and violence, mental health problems, conflict with the law, addiction or having no safe place to call home – are often overlooked in policy and services designed to meet young people’s needs, and we hear little about the reality of their experiences.

Time and again, youth policies, reviews and strategies fail to recognise the different and gendered experiences and needs of girls and boys. The Government’s Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision Green Paper, for example, makes no mention of girls – despite the NHS’s own research showing that young women (aged 17-19) are a high-risk group for mental health problems.

Even where it is recognised that girls face poorer outcomes or face additional vulnerabilities that might mean they face further risk, their needs are rarely given the attention they deserve. The Timpson Review of School Exclusion found girls in care were much more likely to be excluded than those not in care – a much clearer trend than in boys. And despite the Charlie Taylor Youth Justice System noting the extreme vulnerability of girls in custody, the Government has no clear plan to address girls needs in the criminal justice system.

Government and the media tend to report on issues affecting disadvantaged young people as though these primarily affect boys, and in many cases the way girls are affected is overlooked. We regularly see models of provision, support and sanctions built around young men’s lives. This is particularly true where girls are in the minority, such as the criminal justice system and pupil referrals units, or where their experiences might be more hidden, such as with intimate partner violence. Overall this means girls are easier to overlook, which translates directly into what gets measured, how policy is designed, who gets heard and what gets funded on the ground.

We need to shift to a more gendered understanding of ‘risk’ and ‘harm’ as it affects young people and wider society. As girls are more likely to be a risk to themselves than to others, for example by self-harming of developing eating disorders, we often don’t see their pain and struggles. If we continue to only think about externalised behaviours such as getting in fights or acting out in school (in themselves also often expressions of trauma), we fail to see the true extent of problems affecting girls.

Unseen and left without help, girls may go on face other problems, coming to the attention of other services such as children’s social care around concerns about their own children, or as adult survivors of childhood exploitation facing the legacy of trauma. The fact that many services working with adult women say the needs of their beneficiaries are increasing, becoming more entrenched and more complex, suggests we aren’t getting things right at an earlier enough stage for girls and young women.

Sadly, we hear similar experiences to the words of Sheena all too often. Girls telling us that they haven’t been seen, understood or helped to fulfill their potential. Which is why Agenda is launching a new programme of work to uncover girl’s lived realities, and generate solutions for change. By growing the evidence base on girls needs and experiences, working with girls to identify what works and what’s needed, and engaging with those in positions of power and influence to put this into practice, we aim to bring about the change girls tell us they want.

If you work with girls and young women facing disadvantage, we would love to hear from you. Please get in touch with [email protected] to find out more and be part of this work.

The decision for the Barrow Cadbury Trust to take another step and become a Living Wage Funder was an easy one for us as we were already a Living Wage Employer. The Trust has a long history of tackling and addressing the root causes of poverty and disadvantage and the Living Wage campaign fits with a number of our over-arching concerns, one of which is tackling gender disadvantage. A majority of the low paid workforce are women. Rather than being heavy handed about our grantees becoming Living Wage employers, we try to support anyone we fund if they’re interested in finding out more. As funders we have both hard and soft power to encourage those we fund to explore becoming a living wage employer.

The process for us to gain accreditation as Living Wage Funder was fairly simple requiring us to make some very small changes. As much of our funding already goes into long term research, policy and influencing work rather than front line, short term direct services, and funding staff posts, we contribute to only a very small number of low paid roles. So for the Trust there is less of an impact on our grant making than there might be for some of the larger volume funders.

We made some small changes to our application and assessment process adding additional questions, and where relevant we have proposed increased salaries to encourage grantholders and prospective applicants to think about building a Living Wage workforce. We signpost those who want to find out more about becoming a Living Wage Employer to the Living Wage Foundation, but we understand that it is not always an easy thing to do and so also offer to cover accreditation fees for smaller organisations.

We have found that the Living Wage Funder scheme is flexible. We‘re a supportive group of trusts and foundations and are very happy to help funders contemplating signing up to think through the implications. As an anti-poverty organisation, it’s important that we use the resources at our disposal to advocate for and encourage the scheme, and to see how we can enable more charities to become Living Wage Employers.

Find out more on how your organisation can join the Living Wage.