Public understanding of social care is low. Many people are unsure what it is – never mind how to get it, or who pays – until they or someone close to them comes to need support beyond what friends and family can provide. A lot of care work goes on behind the closed doors of people’s homes, hidden from view. When it happens in public places, it’s unlikely to have a social care hat on: a dance workshop inclusive of disabled people or an arts club for isolated older people are not ‘social care’ to those involved – they are just a dance workshop and an arts club.

Because of this, the sheer scale of social care can be a surprising fact. The workforce is made up of 1.5 million people, bigger than the NHS. It is a major sector of the economy and a foundational sector too, essential to millions of people. By supporting them in diverse ways, social care provides the ‘invisible scaffolding’ they need to live the life they want, regardless of age or disability.

It is, nonetheless, overlooked by economic policy makers. An obsession with GDP does not favour social care: it’s hard to measure productivity in a sector where outcomes, not outputs, are what counts. The purpose and value of the service gets lost, and it’s treated as a cost rather than an investment. More fundamentally, the people who stand to benefit from public investment in social care are not wealthy. The means test restricts access to those on low incomes, while care workers themselves are generally paid close to the minimum wage. Inequalities in power are central to the undervaluing of care.

The oversight by policy makers is huge, not least because there is vast scope for improvement in social care. The system is failing on many fronts. A market approach incentivises providers to compete to win business, scrambling to undercut each other. Chain companies, whose business models are suited to short-termist, cost-driven, competitive tendering, gain market share. Care worker jobs become more precarious and care itself can resemble a ‘factory production line’, with people needing support having little say or control.

Locally, there are glimmers of hope. A small but growing number of social care commissioners are trying to shift away from the status quo. Other policymakers in local government are developing strategies to build more inclusive local economies. They should join the dots. As a sector rooted in the everyday lives of millions of people, social care has the potential to drive creative new approaches to economic development. The objective of meeting care needs is connected to a lot of other objectives: building local wealth, lifting up job quality, reducing unemployment, improving health and wellbeing, and supporting more connected, resourceful and powerful communities, to name a few.

Our report, published today, explores the benefits to local economies of one particular approach to care. Community micro-enterprises are small social businesses that provide support in diverse ways. In places like Somerset, where they have been promoted by the local authority, they have proliferated – with numbers jumping from around 50 to more than 450 over five years. We find that micro-enterprises can enable personalised care, by devolving decision making to people at the frontline. They also spread an accessible form of entrepreneurship, create roles that offer more autonomy and control than a typical care job, and build resilience, creativity and diversity in social care. In doing so they help to draw people into the sector and encourage them to stay. A third of the micro-entrepreneurs we surveyed doubt they would be working in social care if they hadn’t set up their micro-enterprise. Two thirds expect to continue running their micro-enterprise for five years or longer.

Local authorities have a crucial role to play in supporting the development of ventures like these. They can encourage the spread of micro-enterprises as part of a family of care models that promote inclusive economic development, such as co-operatives, social enterprises and user-led organisations. These models are often locally rooted, they are driven by social purpose, and they generally seek to be accountable to the people they support. Policymakers should not see this as a marginal endeavour: the goal should be a bottom-up rejuvenation of communities and the economies that serve them. This will require long-term public investment, along with willingness to collaborate, experiment and learn.

There comes a point in any crisis where critics on the side-line weigh in to point out all the things that are being done wrong.

To those in the eye of the storm, this can seem like an unnecessary distraction. But I do not think we should wait until the end of the pandemic before seeking constructive feedback, learning from our mistakes or altering our behaviour. It is very possible that our ‘new normal’ will be years of swinging between socially distanced public activity and lockdown. We all need to accept and respond to feedback while the work of responding to the pandemic continues.

But if we are to reflect on where civil society has done well and where it hasn’t, let’s not start by rehashing stale conversations about how ‘professional’ the charity sector is and whether we need to be more ‘business like’. Especially when being business-like hasn’t made the lives of businesses any easier in the last two months.

Instead the conversation should take as a starting point the core purpose of civil society: public benefit delivered for public good, not private gain. Throughout this crisis I have seen the true value of civil society in the volunteers delivering food to people unable to get to the supermarket, in the digitisation of befriending services to support lonely people, in the hospice workers and domestic abuse support staff going to work, risking their health so others can be safe, receive love and feel dignity.

Many civil society staff who have been furloughed have been keen to volunteer their expertise to other not for profit organisations. The generosity I have seen from colleagues across the sector, whether furloughed or not, volunteers or paid staff has continually and repeatedly inspired me.

Lockdown has also thrown a light on the things we value most, things that are too often dismissed as luxuries but are instead the mark of a well, healthy, happy society. Theatres, dance, access to green spaces, museums, community choirs, the local Scout, Woodcraft folk or Girlguiding troop, are all part of civil society. Civil society is already valued, it’s just that most people have no idea what ‘civil society’ means.

Our sector does not need to ape business or the public sector because we are not business or the public sector. In the past some of us umbrella and membership bodies whose role is to champion our distinct identity have been too reluctant to do so because of concern about the complexity of the sector, or fear of being seen as too ‘argumentative’, ‘unreasonable’ or ‘demanding’ by politicians. These are terms that are most often used to put people in their place, they are used by people in positions of power to remind those with less power to be grateful for what they are given, even when it isn’t what they need. All three terms are also highly gendered, classed and racialised.

The lack of knowledge and understanding about the role of civil society in central government has been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic. But we cannot expect politicians to understand the distinct nature of civil society if we do not shout about it. Similarly, we cannot complain that government expects solutions for businesses to fit charities if we are always talking publicly about trying to be more ‘business-like.’

By centring people and the environment in discussions about how the sector can improve we will build back better.

Some, but by no means all, of the questions I think are important for the sector to be reflecting and acting on now are:

- Who is at highest risk of experiencing harm and are civil society organisations reaching them? If not, why not?

- Who are the voices with access to power and are they representative of the people we serve?

- Is funding distributed by civil society being distributed equitably?

- Why doesn’t government understand civil society and how can we change that?

- How do we build on the strengths of the sector’s response to Covid-19 and learn from our failures?

It is also important to remember that many of the problems we are lamenting now existed before Covid-19. Civil society has seen its political influence gradually decrease for at least 10 years. Ways of working that were effective in the past will not work now. Part of being a good leader is a commitment to continuous learning.

So come and talk to us about how we build on the amazing strengths of the sector and address the weaknesses and the challenges. Wouldn’t it be something if in the future the government pointed at the voluntary sector and told businesses they need to be more like us?

To celebrate the Barrow Cadbury Trust’s steadfast one hundred years of social justice, this was to be a blog about prison reform – a cause so generously supported and well understood by the Trust throughout its history. Instead it is a call to Government to save lives.

I would have covered the painstaking steps taken since the Woolf report – appropriate since the publication of this blog, 1st April, coincides with the start of the disturbances at Strangeways prison thirty years ago. I could have celebrated the tremendous drop of over 70% in child imprisonment and the corresponding reduction in youth crime in recent years. Locking up children is the surest way to grow the adult prison population of the future. I could have welcomed, and documented, a growing acknowledgement that prison should not be used as a place of safety for vulnerable people who are mentally ill or those with learning disabilities and all forms of neurodiversity.

I could have bitterly regretted the swingeing budget cuts that put paid to access to justice and legal aid; stripped the prison service of over 30% of some of its most experienced staff and served to fuel a tragic rise in violence and suicide in custody. Recorded incidents of self-harm reached a staggering 61,461 in the year to September 2019. And I could have explored what needs to be done to reform the criminal, and wider social, justice system to support victims, people who offend, families, prison staff and volunteers in our least visible, most neglected, public service.

Instead when the lives of people in custody and the staff who look after them are at risk, this blog is about survival, leadership and accountability. As Covid-19 spreads, Ministers and officials are faced with some of the most difficult decisions they have ever had to make about balance of risk and the best ways to keep people safe.

To meet its human rights obligation to take active steps to protect lives, Government must embark without further delay on, and give a clear public explanation for, a programme of planned prison releases. This should be done on a cohort by cohort, case by case basis. People who should be considered for immediate safe release include those near the end of their sentences; those serving short sentences; or held on remand, for non-violent crimes; those recalled for technical breach of licence; those who are elderly often with co-morbid health conditions; pregnant women and mothers and babies – where an important start is at last being made. For individuals approved for, but still awaiting, transfer from prison to psychiatric care (a comparatively small group but in high need and one that inevitably makes for disproportionate calls on staff time) this work should be expedited.

The priority now is to reserve prison for serious and violent offenders so that the public is not put at risk and hard-pressed prison governors and staff have the physical space and time to hold those individuals safely and securely. In the context of a global pandemic, countries worldwide from South Korea and Iran to the US and Canada, from Holland to Ireland and Northern Ireland have already released thousands of prisoners variously on a temporary, compassionate or executive basis.

Meanwhile the prison service in England and Wales has made commendable and rapid moves to improve, amongst other things, hygiene and cleanliness, communication with prisoners and phone contact with families to mitigate against further isolation and distress. Emergency use of other secure environments is being explored. Notwithstanding these important steps, in an unprecedented public health crisis it is not fair or proportionate to condemn prisoners, and staff responsible for them, to try to survive in insanitary, overcrowded institutions devoid of independent oversight.

Prison and family charities, supported by the Barrow Cadbury Trust and other charitable foundations are receiving heartfelt pleas for help. At the Independent Advisory Panel on Deaths in Custody we have just received two such requests:

‘My husband is on remand we need help. We are all very worried. Fears of loosing our loved ones with out seeing them. Prisoners are dying because of the virus, who can guarantee that my husband will be safe. Trials not happening, nobody knows when this all will happen and finish. Please help’

‘We want them home we are all alone please help us to be with our family. We are all locked down. Please help please raise this issue in the parliament’.

People are sent to prison to lose their liberty not their lives. We look to Government Ministers to exercise moral leadership, to meet their human rights obligations and to accept full responsibility for the lives of people held in state custody.

At Fawcett we have a long history of involvement in the women’s movement, beginning in 1866 with Millicent Fawcett at the age of 19 collecting signatures on a petition for votes for women. Over the past 150 years women have had to fight for every step of progress that has been made. That progress has been considerable. Property rights, access to the professions, access to higher education, the right to vote, equal pay, all women shortlists, outlawing rape within marriage, up-skirting legislation … the list goes on. But despite this progress equality still feels like a distant prospect. This is because structural barriers to women’s equality remain. The focus on individual rights rather than those all-powerful systems and structures means we have at times sat back and thought, ‘we’ve outlawed that, job done’. Job only just begun would be more accurate. So we need interventions which remove or overcome those barriers and we need attitudinal change to embed them.

Structural inequality is when discriminatory practices, attitudes and behaviours are baked into an organisation or system. The way it operates day to day discriminates against women and perpetuates gender inequality. So in the workplace, how this works in practice is that women are undervalued across the economy. As a result, the jobs they do are valued less and they earn less than men. Women cannot know if they are being paid equally at work because they do not know what their male colleagues are earning. So we want to see a new, enforceable ‘Right to Know’, so that women can find out about pay discrimination and resolve it with their employer without having to go to court.

Senior roles in particular, but also certain professions, are designed to be long-hours jobs. But we could design work differently if we chose to. At Fawcett we have called for all jobs to be flexible by default unless there is a good business reason for them not to be, including opening up senior roles to part-time work. This would normalise flexible working and move us from it being something a minority of workers have, to something for the majority.

Creating a parental leave and childcare system that presumes equal responsibility in caring for children would represent a big systemic change. At the moment the system presumes the mother is the main carer and dads have just 2 weeks paid paternity leave plus shared parental leave but only if the woman chooses to give up some of her maternity leave. We want to see a longer, better paid, period of leave reserved for dads, and a more generous, supportive system for all parents and carers, underpinned by investment in our childcare infrastructure.

Ending violence against women and girls is critical for women to achieve gender equality. The fear of male violence and its impact distorts our society and is a huge cost to women, children and to the economy. There is still a prevailing blame culture, objectification is rife throughout women’s and girls’ lives, and gender-based violence has become normalised rather than regarded as unacceptable. The importance of campaigns such as the #MeToo movement to raise consciousness and support survivors of abuse, and challenge and change attitudes, is a hugely important challenge to this cultural norm. It is about individual and organisational accountability. Harvey Weinstein has been found guilty, but so should the film and insurance industries which protected him. This is what systemic change would look like.

Finally, equal power is the key to unlocking the changes we still need. Evidence shows that where women are in decision-making positions they are more likely to make decisions which have a positive impact on women’s lives, tackling issues such as childcare or domestic abuse. So we have to get more women into politics at local and national level. Interventions such as ‘all women shortlists’ have been extremely effective in creating a step change in this. But we also have to address what is still a toxic culture in our politics and wider public debate. So reforming parliament and local government, online harms regulation, political party accountability and transparency, including collecting and publishing diversity data, are all critical if we are to see lasting societal rather than just personal change.

Sam Smethers, Chief Executive, the Fawcett Society

http://www.fawcettsociety.org.uk Twitter: @fawcettsociety

In 2015, Ireland became the first country in the world to bring in same-sex marriage by a popular vote. A referendum where 62.07% of the electorate voted in favour of the amendment to extend civil marriage to same sex couples. This achievement built on years of activism which had succeeded in persuading the political system of the need to change our constitution and why the question should be put to the Irish people. We learnt many things from the campaign and here are some of my take-aways.

Communicate across difference – we learnt that we had to answer the questions in the minds of the voters. We had to listen to what those concerns were and then answer them in a language that appealed to each particular audience. We learnt that people need to see the relevance of the issue within the context of their own experience, the need to connect the campaign goal to the lives of ordinary citizens. The job of the campaign was how to link the struggle with the concerns of regular Irish people. We took on a divisive issue, a minority issue, and made it everyone’s business – your child, your cousin, your friend and your colleague. The campaign gave a glimpse of the kind of nation we could have, connecting with that basic human desire to achieve one’s better self.

Understand how attitudes are shaped and who we had to target and how. Our communications strategies were grounded on solid research that reflected the concerns, values and priorities of those we were trying to influence, especially the middle ground, undecided voter. The research was crucial in shaping the campaign’s message, tone and shape, to appeal to these voters.

Story telling was at the core – the campaign put personal stories at its heart. Exit polls showed the individual stories of those excluded from marriage equality played a huge factor in many people voting in favour. In this age of digital democracy, we learnt that large numbers of facts can be overwhelming. With so much so-called “truth,” the influencing value of personal stories was key to cutting through the noise and distraction.

Messengers were picked for their ability to talk to the undecided. These were complemented with surprising messengers – those who people didn’t expect to hear – and they influenced and connected with the middle ground. We found “unlikely” messengers worked well. We put a spotlight on the voices of “permission givers” like athletes, celebrities, faith leaders, the conservative parent of a gay son or lesbian daughter, and other role models, including the a former President of Ireland as a mother of a gay son.

We learnt to use our feet – the issue was forced onto the political agenda by thousands of activists up and down the country. These activists ran stalls, marched, organised, leafletted, canvassed, shared their stories and made so much noise they could be ignored no longer. It was these individuals that built the power for the referendum result.

We learnt that smart social media mattered – a cutting-edge social media strategy and smart use of analytics also ensured our campaigns had advantage. We channelled a nationwide army of voluntary effort by implementing a technology-assisted and monitored canvassing operation. Crowd-funding paid for our work. Social media gave us opportunities to tell personal stories, promote messages, and communicate with our supporters. The strategy also allowed individuals to be involved at their own pace.

In conclusion: we can never take these wins for granted and there is of course so much work still to be done. But we have lived through great social justice change in recent years, which is certainly cause for celebration. And 20 years ago it would not have seemed conceivable that so many countries would embrace such change.

Denise Charlton (http://denisecharltonassociates.ie) is an activist and consultant working in the area of Social Change and was co-founder of Marriage Equality.

I’ve been talking with people about climate change for more than thirty years. Recently, one question has started to dominate all others: “what is it that I need to do?” We know climate change is happening, we know it’s serious, and we know we all have a responsibility – so what is it that I need to do? The Funder Commitment on Climate Change arose out of several charitable funders, including the Barrow Cadbury Trust, seeking an answer to that question.

In June 2019, at a gathering of foundation leaders, we heard persuasive evidence not only about the threat from rapid climate change, but also of the opportunities and costs of the necessary transition to a low carbon economy. For over a century, our economy and society has been shaped by the use of fossil fuels for electricity, heating and transport. Ending fossil fuel use therefore involves economic and social transformation. Similarly, moving from today’s agriculture to a more sustainable, mainly plant-based food system will also be a huge change.

In the coffee break, several of us got talking about “what it is we need to do” and the idea of a climate pledge or manifesto for funders was born. I offered to start the ball rolling, and was inspired by the amount of energy and interest it attracted.

Conversations continued over the summer. An early realisation was that the pledge had to be inclusive, and relevant to all foundations, whatever their size, governance or charitable mission. At the same time, it was vital to get beyond vague intentions, and several of the founding signatories rightly pushed for high ambition. We also agreed that the Funder Commitment needed to be holistic, recognising all aspects of our work – programmes, investments and operations – will need to change.

The language evolved through discussion and consultation. Initially known as a ‘manifesto’, we eventually settled on the term ‘Commitment’ as having the right connotations. We sought language that would speak to diverse audiences, mindful of the need to build a broad movement. The final text recognises opportunities, such as new industries and jobs, for example.

The Association of Charitable Foundations generously offered space at their annual conference in November to launch the Funder Commitment. This gave us both a platform and a deadline! The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation provided some seed funding, and Comic Relief supported the creation of a website. The final text, founding signatories and communications came together, all just in time.

On 6 November 2019, the Funder Commitment on Climate Change was launched in a packed room of foundation staff and trustees, with many more turned away at the door through lack of space. By the end of the day, inquiries were coming in from other foundations wishing to add their name. At the time of writing, we have topped thirty signatories, with Comic Relief the latest to join.

So, what have we all pledged to do, and why?

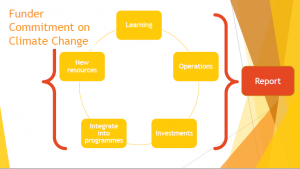

Addressing climate change needs large scale, urgent action. Money is needed for activism, for advocacy, for education, for business development, for practical action, and to support local communities through transition. Some foundations can provide grants, while others can give staff time or other in-kind support. So one element of the Funder Commitment is to commit resources. The slide below illustrates the way it works.

The causes and solutions of climate change interact with many other fields of civil society activity, ranging from housing to the arts, and from scientific research to social change. Foundations have an opportunity to build on their existing expertise and networks, to make productive links across different fields, and to foster positive action on climate in their own priority areas. Another part of the Funder Commitment is about this integration.

Next we come to foundation investments. Climate change is recognised as a risk to investments by the World Bank and Bank of England, amongst others. It is basic good stewardship to recognise and address this risk, and this is what the Funder Commitment requires. There are also many opportunities for foundations to take a more active leadership stance on responsible investment.

While for most foundations, our direct carbon footprint will be small relative to the impact we can have through our grants and investment choices, it is still important and empowering to get our own house in order – to show leadership, to engage stakeholders, and to manage reputational risks. So the Funder Commitment also covers the climate change impact of our own operations.

Every funder, and indeed every NGO, public body and commercial company, will be at a different stage in tackling climate change. This is an ongoing generational transformation, not a one-off task. For this reason, the Funder Commitment opens with a commitment to learning, and closes with a commitment to reporting on progress. What is it that you need to do?

Nick Perks

Find the full text of the Funder Commitment on Climate Change and list of current signatories here.

Nick Perks is a freelance charity and philanthropy consultant.

http://www.nickperks.org.uk/ @Nick_Perks_

Is a growing economy something to celebrate when the benefits it brings are out of reach to many? While the economy grew as a whole in the 2017/18 financial year, the poorest 20 per cent of the population actually experienced a real terms decline in their incomes of 1.6 per cent. Some two-thirds of the jobs created by Britain’s much-heralded, post-recession jobs boom have come in the form of ‘atypical employment’, such as gig economy work and zero-hours contracts. The Government has started to turn its attention to reducing regional imbalances in economic growth, but years of inaction have given them a mountain to climb – the only regions where productivity is above the UK average are London and the South East.

In recent years, policy-makers have started looking beyond usual growth measures (such as GDP and employment figures) towards new approaches that enable more people to contribute to and benefit from economic growth. ‘Inclusive growth’ is the umbrella concept bringing together many of these approaches. NLGN’s latest report, Cultivating Local Inclusive Growth In Practice, supported by Barrow Cadbury Trust, features examples of some of the projects currently being led by councils throughout England. This animation will give you an overview of the project.

The report is structured around NLGN’s new Framework for Cultivating Inclusive Growth. We designed the Framework to be a practical tool to help councils develop their thinking, no matter whether they are just starting to develop a strategy or are in the process of implementing one.

The Framework identifies the groups councils should work with to promote local inclusive growth:

- Employers. These are private, public and third sector organisations of all sizes who employ people in the local area.

- Citizens. These are the people who live and/or work in a local authority area.

- Partners. These are the organisations that work with councils to deliver public services and other projects, such as the NHS, schools and colleges, and companies that have been awarded a contract by the council.

- Places. These are parks, buildings, town centres and other forms of physical space and assets in an area.

These are set against the levers councils can use, with the powers and resources currently at their disposal, to promote local inclusive growth:

- Regulate. This category covers the hardest policy levers at a council’s disposal, including their ability to set rules and regulations to promote inclusive growth. For example, one council uses its procurement process to ensure that only businesses paying the real living wage can successfully apply for council contracts.

- Incentivise. Councils can offer incentives, financial or otherwise, for employers, citizens and partners to behave in a way that is conducive to promoting inclusive growth. For example, one council offers undergraduates and recent graduates of local universities a wide range of paid placement and training opportunities to encourage them to stay in the area.

- Shape. Councils can reshape their area to promote inclusive growth, either literally, through things like redevelopment, or in more subtle ways, through efforts to encourage employers, citizens and partners to promote inclusive growth. For example, some councils have created charters setting out socially responsible business practices and invited local employers to sign up to them.

- Facilitate. Councils can promote inclusive growth in a more ‘back-seat’ facilitative role, by creating the partnerships, institutions and frameworks to enable others to take the lead. For example, one council worked with partners to set up a fund for projects that help local communities access employment, education and training opportunities.

Each section of the report contains many more practical examples and case studies.

We are very grateful to the council officers and think tank/academic researchers whose experiences and insights generously shared with us through interviews and workshops were invaluable to our research. If you have any questions about our research or would like to talk to us about our inclusive growth research, please get in touch with us at [email protected].

In the last year as a board we have also been reflecting on our responsibilities as trustees of a family philanthropic endowment. We have questioned how we exercise our mandate and fulfil our role in the public domain when our endowment is derived from private wealth and as charity trustees, we are unelected.

We are still governed by a largely family board, descendants of the founders, Barrow and Geraldine Southall Cadbury, but are supported by non-family trustees. We recognise that board membership is both a privilege and a service and have taken steps to minimise the impact of that privilege.

Firstly, we recognise that this is not primarily ‘our’ money. It is held in trust for the public benefit and we must approach how we use it with care and humility, consulting and learning from our stakeholders and partners every inch of the way.

Secondly, the staff and trustee board endeavour to minimise the negative power imbalance in our relationships with all of our partners. We hope, as our stakeholders and partners, you’ll let us know when we fall short.

Thirdly we are committed to enhancing our skills as trustees so that our decision making is informed and responsible. Our non-family trustees augment our knowledge base and our perspectives. We also now ask family members who want to join the board to gain experience by serving a governance apprenticeship in a front-line charity.

Most importantly though, we consider ourselves to be an integral part of civil society. We believe we add value as actors, not just as observers or supporters, but in our own right, as all citizens are entitled to.

Over the past few months, as we prepared for the centenary, we reflected with great care on our long term goals and as trustees took the decision to protect the long term future of the endowment. In order to do this, we will have to reduce our spending from our capital to ensure that we have an adequate income in the future. We will do this gradually over our next five year strategic period. We have started to deliver several programmes now for other funding bodies, and we hope to develop this approach further.

As we embark on a new decade, we’ve also been impacted afresh by the surge of younger people renaming the climate crisis as an emergency. The Quaker activist John Woolman wrote presciently in the 18th century “the produce of the earth is a gift from our gracious creator to the inhabitants and to impoverish the earth now to support outward greatness appears to be an injury to the succeeding age”. In this spirit, last year we became founding signatories to the Funder Commitment on Climate Change and will be working over the coming months to translate that commitment to more action.

And in the midst of political turbulence and social division, I would like to draw your attention to the Decade of Reconnection, orchestrated by a number of our partners and others. Launching officially in the Spring, its purpose is to make deliberate efforts – all of us – to reach out respectfully to those who do not share our views. Let us reach out more and listen harder in the interests of a better future.

This blog is the first in a year-long series, drawing on ambitious and clear-sighted thinking and activities from a broad range of our partners, stakeholders and grantees – past and present. We are also delighted to launch our new animation ‘hot off the press’ which we hope captures how we arrived at this place, and very importantly where we’d like to be in another hundred years.

Erica Cadbury

Chair, Barrow Cadbury Trust

“They should have dealt with things properly. They should have listened to what I had said…I wouldn’t have gone through the things that I went through.” – Sheena

Girls and young women facing the greatest forms of inequality and disadvantage are frequently marginalised, ignored and misunderstood. Girls facing a combination of problems – like abuse and violence, mental health problems, conflict with the law, addiction or having no safe place to call home – are often overlooked in policy and services designed to meet young people’s needs, and we hear little about the reality of their experiences.

Time and again, youth policies, reviews and strategies fail to recognise the different and gendered experiences and needs of girls and boys. The Government’s Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision Green Paper, for example, makes no mention of girls – despite the NHS’s own research showing that young women (aged 17-19) are a high-risk group for mental health problems.

Even where it is recognised that girls face poorer outcomes or face additional vulnerabilities that might mean they face further risk, their needs are rarely given the attention they deserve. The Timpson Review of School Exclusion found girls in care were much more likely to be excluded than those not in care – a much clearer trend than in boys. And despite the Charlie Taylor Youth Justice System noting the extreme vulnerability of girls in custody, the Government has no clear plan to address girls needs in the criminal justice system.

Government and the media tend to report on issues affecting disadvantaged young people as though these primarily affect boys, and in many cases the way girls are affected is overlooked. We regularly see models of provision, support and sanctions built around young men’s lives. This is particularly true where girls are in the minority, such as the criminal justice system and pupil referrals units, or where their experiences might be more hidden, such as with intimate partner violence. Overall this means girls are easier to overlook, which translates directly into what gets measured, how policy is designed, who gets heard and what gets funded on the ground.

We need to shift to a more gendered understanding of ‘risk’ and ‘harm’ as it affects young people and wider society. As girls are more likely to be a risk to themselves than to others, for example by self-harming of developing eating disorders, we often don’t see their pain and struggles. If we continue to only think about externalised behaviours such as getting in fights or acting out in school (in themselves also often expressions of trauma), we fail to see the true extent of problems affecting girls.

Unseen and left without help, girls may go on face other problems, coming to the attention of other services such as children’s social care around concerns about their own children, or as adult survivors of childhood exploitation facing the legacy of trauma. The fact that many services working with adult women say the needs of their beneficiaries are increasing, becoming more entrenched and more complex, suggests we aren’t getting things right at an earlier enough stage for girls and young women.

Sadly, we hear similar experiences to the words of Sheena all too often. Girls telling us that they haven’t been seen, understood or helped to fulfill their potential. Which is why Agenda is launching a new programme of work to uncover girl’s lived realities, and generate solutions for change. By growing the evidence base on girls needs and experiences, working with girls to identify what works and what’s needed, and engaging with those in positions of power and influence to put this into practice, we aim to bring about the change girls tell us they want.

If you work with girls and young women facing disadvantage, we would love to hear from you. Please get in touch with [email protected] to find out more and be part of this work.

Pay for the typical FTSE 100 CEO in 2020 has already surpassed the amount the average UK worker earns in an entire year. High Pay Centre argues that much more can be done to achieve a better balance between those at the top and everybody else, in this blog originally posted on High Pay Centre website on 5 January.

FTSE 100 CEOs only need to work until just before 17.00 on Monday 6 January 2020 in order to make the same amount of money that the typical full-time employee will in the entire year.

The calculation for ‘High Pay Day 2020’ is based on research by HPC and the CIPD, the professional body for HR and people development, showing that:

- Top bosses earn 117 times the annual pay of the average worker

- In 2018 (latest available data) the average FTSE 100 CEO earned £3.46 million, equivalent to £901.30 an hour

- In comparison, the average (as defined by the median) full-time worker took home an annual salary of £29,559 in 2018, equivalent to £14.37 an hour

- To match average worker pay in 2020, FTSE 100 CEOs starting work on Thursday 2 January 2020 only need to work until just before 17.00 on Monday 6 January – just three working days (33 hours)

High pay will be a key issue in 2020 as this is the first year that publicly listed firms with more than 250 UK employees must disclose the ratio between CEO pay and the pay of their average worker. Under changes to the Companies Act (2006), firms must now provide their CEO pay ratio figures and a supporting narrative to explain the reasons for their executive pay ratios. The first round of reporting will be seen in annual reports published in 2020.

Compared with last year, CEOs now have to work slightly longer to make the median UK salary, after their pay fell from £3.9 million. However, the fact that it now takes them until teatime, rather than lunchtime, on the third working day of the year to pocket a sum of money that half of workers did not earn for an entire year’s work in 2019 rather puts this slight fall into perspective.

How major employers distribute pay across different levels of the organisation plays an important role in determining living standards. CEOs are paid extraordinarily highly compared to the wider workforce, reflecting an approach to business that has made the UK one of the most unequal countries in the developed world.

If we want to raise incomes for low and middle earners, measures that will enable them to get a fairer, more proportionate share of the spend on pay distributed by big companies will be of critical importance.