Last week Home Secretary Suella Braverman urged police forces to increase the use of stop and search. In a statement addressed to all 43 forces across England and Wales, Braverman stated that officers would have her “full support” to increase use of the tactic.

While the Home Secretary cannot make police forces increase the use of stop and search, as they operate separately from government, it will undoubtedly impact young, Black boys, men and other ethnic minority people, who are disproportionately targeted by police when using stop and search powers.

Suella Braverman’s statement has come soon after His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) published its annual ‘State of Policing’ report which assesses policing in England and Wales in 2022.

In his report, Chief Inspector of Constabulary Andy Cooke described widespread systemic failings in both the police and the criminal justice system, and called for ‘definitive action’ which would address these failings and seek to restore public trust in the police force.

Failures to fulfil basic, fundamental duties and issues with governance and leadership were highlighted as key issues, as well as a need to target resources on crimes that ‘matter the most to the public’.

Despite acknowledging systemic failings across the criminal justice system, the annual report crucially fails to meaningfully reflect on racism and the detrimental impact institutionally racist practices have had, particularly on young Black men. Rather, the Chief Inspector encouraged the use of stop and search powers, deeming it an effective crime deterrent, even if it “polarises the public”.

The Chief Inspector went on to note that disproportionality in stop and search rates could not be explained by disproportionality in crime victimisation rates – with people from Black, Asian or ethnic minority communities almost twice as likely as the wider public to know a knife crime victim or to have been one themselves. This was not evidence of racism within policing, the Chief Inspector said.

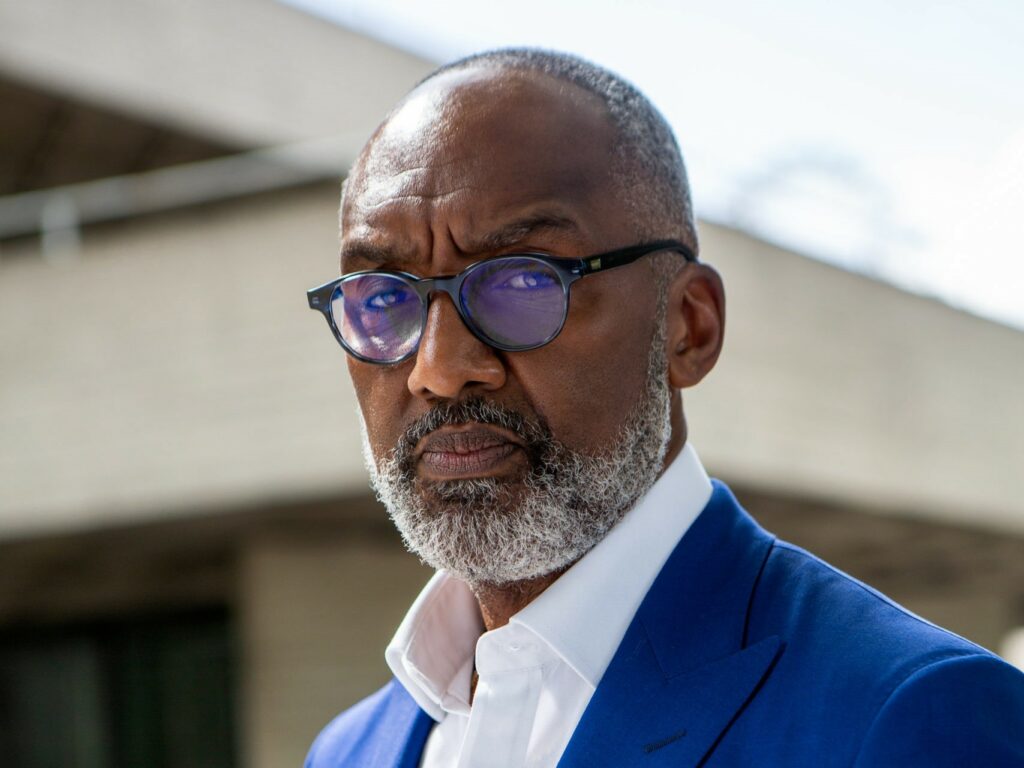

“There needs to be better evaluation and more research to measure disproportionality and the effectiveness of stop and search to fully understand how it affects certain communities and deters crime…This research could have a meaningful effect on police practice and help forces make sure that they use stop and search effectively and fairly.”

Chief Inspector of Constabulary Andy Cooke QPM DL

But we already have the research. According to Home Office data published on stop and search and arrests for year ending 31 March 2021, individuals from a Black or Black British background are seven times more likely to be searched than those from a White ethnic group. Under Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994) powers, which allow for ‘suspicionless’ searches, disproportionality doubled, with Black people being fourteen times more likely to be searched.

Moreover, the government’s own research suggests that stop and search is not an effective deterrent in reducing offending.

It is disappointing to see a lack of reflection on, or acknowledgement of, racism within policing in the ‘State of Policing’ report. It follows the recent unwillingness of prominent police and governmental figures to accept the existence of institutional racism in policing.

In March, the Casey Review, a year-long investigation into the standards of behaviour and internal culture of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), found the MPS to be institutionally racist, sexist and homophobic.

MPS Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley refused to accept the terminology used by Baroness Casey, but the review confirmed what Black communities, women and members of the LGBTQ+ community have known for decades – policing is broken.

Acknowledging the existence of institutional harm is just the first step in a significant journey which police forces across England and Wales will have to take in order to regain the public confidence that is necessary to effectively police. That’s why we welcomed chief constable Sarah Crew acknowledging that her own force, Avon and Somerset Police, is institutionally racist.

With two out of the 43 police forces having been formally described as institutionally racist, other forces would do well to review services in line with the criteria used within the Casey review and accept reality.

Beyond this basic recognition, there is an urgency for the government to identify and enact effective policies which will tackle violent crime without discriminating against young Black, Asian, and mixed heritage people. This should start as early as the classroom – reversing cuts to education and ending exclusions, in order to foster a society which values our young people, rather than criminalising them as children.

For Action for Race Equality (ARE), having a more equal society means young people will be able to believe that their race, ethnicity or faith will not limit what they can achieve in life, and I look forward to helping the organisation work towards this goal in my new role.

Author: Meka Beresford, Head of Policy