Young Adults

We are looking for a skilled and proactive communications consultant to lead and coordinate the communications work across our criminal justice programme, with a particular focus on T2A.

Background

Barrow Cadbury Trust’s criminal justice programme includes a range of initiatives focused on improving outcomes for young adults and addressing systemic inequalities in the criminal justice system. A key strand of this work is the Transition to Adulthood (T2A) campaign, which promotes a distinct approach to policy and practice for young adults. Alongside T2A, the Trust also supports the Young Adult Justice Team (YAJT) project and cross-cutting work on racial and gender justice.

T2A has made significant progress over the past decade in embedding the principle that young adults have distinct needs within criminal justice policy. However, implementation in practice remains inconsistent. To address this, we are seeking a communications consultant to help amplify our messages, promote our extensive body of research and tools, and support the next phase of our work. Further details of our work can be found at www.t2a.org.uk.

About the Role

We are looking for a skilled and proactive communications consultant to lead and coordinate the communications work across our criminal justice programme, with a particular focus on T2A. This includes managing and developing our digital presence, supporting media engagement, and helping to shape and deliver strategic communications that influence policy and practice.

This role will work closely with the Head of Criminal Justice and the Head of Communications and liaise with our wider network of partners.

Over the next year, we’re focused on four key priorities:

- Synthesising 20 years of T2A evidence into a clear, actionable vision for young adult justice, and embedding systems change across policing, prisons, probation, public affairs and public policy.

- Embedding lived and learned experience at the heart of our work through a new T2A Alliance advisory panel and group.

- Advancing racial and gender justice by challenging systemic bias and centring equity in all we do

- Driving strategic communications to support the next phase of T2A and counter harmful narratives.

Key Responsibilities

Social Media and Digital Engagement

- Develop and deliver content across a range of social media platforms (e.g. LinkedIn, Bluesky, Substack, Telegram, YouTube, TikTok, Facebook, Snapchat), tailored to reach criminal justice policymakers, professionals, wider public and young adult audiences.

- Manage and grow the T2A and wider criminal justice LinkedIn presence.

- Liaise with funded partners and stakeholders to support and disseminate their work.

- Create engaging content including infographics, videos, and visuals.

- Monitor and report on social media analytics monthly.

- Build and maintain relationships with key stakeholders and influencers online.

Website and E-Comms

- Maintain and update the T2A website and contribute to other relevant digital platforms.

- Draft and source content for e-newsletters and alerts.

- Monitor website analytics and provide regular performance reports.

Multimedia and Publicity

- Draft press releases, newsletters, and other promotional materials.

- Identify and pursue opportunities for media coverage in specialist and mainstream outlets.

- Record and evaluate media coverage and campaign impact.

- Support the development and delivery of podcasts and webinars.

- Attend and support T2A and criminal justice-related events and launches.

Strategic Communications

- Work with the team to synthesise 20 years of T2A evidence into a compelling vision for young adult justice.

- Support the integration of lived and learned experience into communications.

- Help challenge harmful narratives and promote racial and gender equity in criminal justice.

Audience Engagement

- Support audience research and analysis to inform communications strategy.

- Develop materials to increase visibility and engagement with key stakeholders.

Person Specification

Essential Skills and experience

- Demonstrable communications skills and experience. This could include professional roles, freelance work, or self-initiated projects. We welcome applications from individuals who are self-taught or have taken non-traditional routes into communications.

- Strong digital communications skills, including social media strategy and website content development.

- A particular interest and experience in social media and digital comms, including updating, drafting and developing website content.

- Experience in either the criminal justice sector or working with local or national government, policy, or mainstream media.

- Excellent written and verbal communication skills.

- Ability to work independently and collaboratively with a range of stakeholders.

Terms

This is a minimum 6-month consultancy role with an indicative time commitment of up to 8 days per month. We anticipate an initial budget of up to £25,000 for an initial 6-month contract, with a view to ongoing work. This equates to a day rate in the region of £300–£400, depending on experience. The consultant will be expected to attend fortnightly meetings at the Trust’s offices and participate in monthly campaign management meetings online. We also anticipate this being a medium- to long-term relationship for the right partner.

How to apply

Please send your CV and a covering email or letter (maximum 2 sides of A4) to [email protected] outlining

- Your interest in the role

- Relevant experience

- Your daily rate (including VAT if applicable

Deadline for applications: 12 noon on Thursday 30 October 2025. We anticipate holding interviews on Thursday 6 November, with an immediate start from 10–12 November, including participation in a team retreat event in Oxford.

If you have any queries about this role, please contact [email protected] or [email protected]

The Alliance for Youth Justice briefing ‘Adultifying Youth Custody: Learning lessons on transition to adulthood from the use of youth custody for young adults’ explores how the Government’s decision to temporarily raise the age young people transfer from the children’s secure estate to the adult secure estate from 18 to 19 resulted in a 253% increase in the number of over 18s in the child estate. The briefing highlights the lost opportunity for systemic reform during this time and warns of the long-term risk of blurring the boundaries between youth and adult justice systems.

Key recommendations include:

Custody as a last resort

The Ministry of Justice must recognise the vulnerability and potential victimisation of children and young people who come into contact with the law, along with the genuine harm imprisonment brings. Where imprisonment is unavoidable, custody should treat children as children, with an emphasis on rehabilitation over punishment. Secure Children’s Homes must become the norm.

Remove the Youth Custody Service from HMPPS and create a Department for Children:

Child First policies must be at the heart of youth justice, so we’re calling on the YCS to be removed from HMPPS. We propose a new Department for Children to bring the care of all vulnerable children into one place.

Ensure the distinct character of the children’s secure estate, keeping it separate from the adult secure estate:

The children’s secure estate cannot become an overflow for a failing adult prison system. The children’s secure estate must be restricted for the care of under 18s only, other than on a case by case basis.

Develop a comprehensive plan for young adults in custody:

With the lessons learned from the temporary transitions policy change, HMPPS must create a far-reaching policy that addresses young adults’ distinct needs, entitlements, and maturity. The Ministry of Justice should conduct a review of domestic and international models for young adult custody to determine the most effective approach.

Supportive transitions on a case-case basis:

The Ministry of Justice must identify all barriers to case by case decision-making on when a young person transition from youth to adult custody. These decisions must always centre the individual young person’s wants and needs. There also needs to be continuity in the education, youth work provision and other services they are able to access when making the transition.

Background

A new MoJ ‘process evaluation’ of Newham Y2A Probation Hub, a specialist youth to adulthood transitions service, which Barrow Cadbury Trust’s T2A (Transition to Adulthood Alliance) has supported for several years, has concluded that it is a successful model. The process evaluation took two years to look in detail at the implementation of this specialist young adult Hub in East London.

The model is based on T2A evidence of what works for young adults. Over the last 20 years, T2A has focused on how best justice services can support young adults to build positive lives away from crime. T2A’s core ask is for a distinct service that takes the best elements from youth justice services and develops them for young adult use. These services would be ‘young adult first,’ trauma-informed, strengths-based, and build strong pro-social identities.

The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), with support from the Ministry of Justice, London Probation Service and the Treasury’s Shared Outcomes fund, set up the Hub in March 2022 to respond to the specific needs of young adults on probation in Newham. It was purposefully and carefully designed to meet the specific needs of young adult, with input from young adults themselves.

The set up

A purpose-built space was developed so that young adults could be supported separately to older adults. Young adults were consulted during the design stage and all staff had specialist training in trauma-informed practice, neurodiversity, and developmental maturation. Staff worked with young adults on strengths-based and future-focused approaches. Flexibility around breach and enforcement was part of the ethos, and young adults’ successes were celebrated – a model adapted from youth justice services.

Alongside the mandatory service provided by probation, probation staff also supported young adults to access voluntary sector services such as mentoring and coaching, speech and language support, restorative justice, and housing support, along with education, training, and employment advice. Those young adults with mental health needs or who face extra neurodiversity challenges could access creative therapy.

Findings

Barrow Cadbury Trust’s ambition in supporting this project was that the Hub would be a template for the delivery of probation services to young adults across England and Wales.

The key finding of the process evaluation, was that the Hub had the potential to shape young adults’ maturational development and enable them to develop self-belief, build resilience, and regulate their behaviour.

Staff were positive about the impact of the Hub on young adults’ compliance and engagement, notably in the successful completion of sentences, as well as on young adults’ lives. The bedrock of the service is developing responsibility and forward planning skills that are all important for desistance. The evaluation found that staff were well-informed about the specific challenges facing young adults and supported them in responding to trauma in an informed, and person-centred way. Multiple services all on one site meant same day referrals were possible, and there were relatively short waiting times for first appointments, so that momentum built early on and made building relationships easier.

The evaluation highlighted the difficult life experiences that these young adults have faced in their short lives, including social and economic disadvantage, poverty and racial discrimination, reflecting the fact that Newham is the second most disadvantaged borough in London. Many had high levels of support needs because of their lack of maturity, their thinking, behaviour, attitudes and lifestyles. The evaluators recognised that these adversities and life changes take time to work through and overcome. Practitioners acknowledged this: “It takes time for young people who haven’t had the same benefits, the positive inputs, the positive attachments, the community. If they haven’t had that, they need time, and time isn’t two years … for long lasting change.”

How the Hub supported young adults

This model of delivering probation services to young adults, where the emphasis is on preparing them for a stable adulthood and independence, is significantly different to the offer available to older adults. Six core values – safety, trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment, and inclusivity are the essence of the Hub’s approach.

Although it is not the function of probation to turn children into adults, probation services can support the goal of reducing offending by assisting in the young person’s journey to independent adulthood. Young adults interviewed had a sense that maturity is something that develops and with the support of the Hub staff they felt empowered to put in place the building blocks to change their lifestyles.

It wasn’t just the young adults who recognised the benefits of the Hub. Staff welcomed the greater professional autonomy and flexibility they had as well as the advantages of holding pre-breach interviews before proceedings were necessary.

Young adults found the Hub a safe and welcoming area to engage, both with their probation officer and in therapeutic activities. This holistic approach made a crucial contribution to long-term positive outcomes. The wraparound support gives young adults the space to grow and learn about themselves.

The evaluation found that the Hub’s emphasises on cultural awareness and gender-specific services was appreciated by staff and young adults. This emphasis ensures that the diverse backgrounds and experiences of individuals are respected and valued, fostering a sense of belonging and understanding. The gender-specific approach recognises the unique needs and challenges faced by women, and how important tailored support is in a separate space, alongside other women’s services.

Outcomes/Experiences

One objective of the hub is to improve partnership working and information sharing between services so that young adults are less likely to fall through the net when children’s services support falls away at 18. The evaluation found that staff were able to develop strong, collaborative, trusted relationships with each other, with a shared purpose, and gain knowledge, formal and informally, from specialist professionals, a greater diversity of partners, as well as tapping into ongoing training and development. Probation officers benefitted from more time with young adults due to smaller caseloads.

The future

So far, more than 400 young adults have engaged with probation services in the Y2A Hub. The evaluation has demonstrated that success or failure of the service cannot be captured solely in reoffending data. T2A agrees with the evaluators that stage-specific services which help young people develop into mature adults are crucial. But we also recognise the importance of finding metrics for a young adult’s growth in their outlook, perceptions, maturity and self-identity.

The fact that staff and young adults interviewed were unanimously in favour of rolling out similar hubs in other parts of London and more widely is testament to the value of the model and the careful evidence-informed work that went into its planning. This is an innovation that the Government should be grasping with both hands, in line with its mission to “reduce the barriers to opportunity” and its ambition to tackle violence amongst young people. And the probation service deserves huge credit for putting evidence into practice and in so doing showing that the principles espoused by T2A have benefited young adults involved in the justice system.

This positive evaluation and the 20 years of T2A’s experience strongly underpin the need for young adults to receive specialist support, delivered in dedicated settings.

‘The starting point is not a goal but a collaboration’ – how Barrow Cadbury Trust has used systems change approaches to tackle complex issues in the justice system.

Young adulthood

How do you explain to people who don’t work in criminal justice about the distinct needs of young adults caught up in that system? Well, we held a mini 18th birthday party in our workshop room with balloons and birthday tunes! We then invited them to think back to when they turned 18 (or when someone they know turned 18).

Their reflections from this exercise were revealing and we identified three main themes:

| Feeling overwhelmed and uncertain

| ‘I didn’t have a bloody clue what I wanted to do!’ ‘It was very overwhelming at 18, I was trying to understand my place.’ ‘Overwhelm and excitement – yoyoing between those emotions.’ ‘I had undiagnosed mental health problems.’ |

| Testing boundaries

| ‘Testing boundaries and not always knowing where the boundary is and the repercussions until you’ve crossed it.’ ‘Experimenting with taking responsibility and consequences – it’s a never-ending journey.’ ‘I had a total lack of fear.’ ‘Learning from role models.’ |

| A social construct

| ‘Are you even really an adult at 18? In Sweden, you’re classed as an adult at 21. Adulthood is a social construct. It varies all over the world.’ ‘Are you really an adult at 18?’ ‘They said – but you’re an adult! I thought, oh great, but I still need help from adults!’ |

One attendee said afterward that they ‘particularly enjoyed the visualisation exercise - I mostly forgot that overwhelming jumble of thoughts and emotions around the age of 18.’

The group in question were attendees at the Systems Innovation Network Global Conference, mainly working in sectors such as health and sustainability, where systems thinking has taken root. Two of Justice Futures co-directors Gemma Buckland and Nina Champion, along with Laurie Hunte from the Transition to Adulthood Alliance at Barrow Cadbury Trust and Nadine Smith, a young justice advisor, were facilitating a workshop exploring how systems thinking can help improve outcomes for young adults in the justice system, and why a systems approach to funding is necessary to tackle complex issues and see transformational shifts.

Nadine explained the distinct needs of young adults in the criminal justice system including the fact that their brains are still developing and that the process of maturity doesn’t end at 18. She described the ‘cliff edge’ of services and support stopping and how young adults are often grouped with adults of all ages, whether in court, in custody or on probation, whereas we have a separate system for under-18s. She discussed her work with the Transition to Adulthood Alliance (T2A) and Leaders Unlocked, ensuring that young adults with lived experience are empowered to influence systems change by conducting research, designing services, and speaking to policymakers.

She set out that this is a complex issue as there is not one solution; it’s interconnected, multi-dimensional, and involves multiple and conflicting perspectives. In systems speak, this is known as a ‘wicked challenge’

The criminal justice eco-system

We then got attendees thinking about the different actors in the ecosystem that T2A works with and their multiple and conflicting perspectives. Using a Si Network Actor Mapping canvas, attendees were asked to imagine themselves as young adults, policymakers and practitioners to think about what values, power, mental models and incentives these actors have in the system when it comes to meeting young adults’ distinct needs.

When looking at power, attendees highlighted various types of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power dynamics including physical violence, money, the law, the power to ‘say no’, and even the power of an officer’s uniform. Incentives varied from hitting targets to ‘respect’, serving the community, to wanting a quick exit from the system. Mental models included ‘do the time, do the crime’, ‘prison works’, crime being caused by individual choice rather than societal failures and the ‘punishment v. rehabilitation’ dichotomy. Lastly, the values influencing actors in the ecosystem noted by participants were protection, risk reduction, efficiency, the rule of law, empathy, and suspicion.

The purpose of the exercise was to better understand what’s going on ‘under the surface’ with different actors in the system, so we can then work with the systemic patterns identified productively to affect change in the system.

As one workshop participant reflected ‘one of the most powerful exercises you can do is to step into other people’s shoes in the system.’ Another commented that ‘the ambiguities that arise are interesting.’ And one said it was ‘eye-opening. I could connect directly with some of the issues I’ve noticed in our neighbourhood. [It was] very effective in helping us look at these issues from different perspectives.’

These insights are what these systems tools are designed to bring out – helping people see differently, think differently and then do differently … our tagline at Justice Futures!

If we’d had more time, we would have discussed the insights the group had gained from examining the system from different actors’ perspectives and then used these to identify which leverage or intervention points would have the most long-lasting, positive impacts on the system. This is something that T2A, supported by the Barrow Cadbury Trust, has been navigating for the past two decades, as set out in a recent evaluation report by IVAR.

Changing the funding paradigm

We also used the actor mapping canvas to explore the values, power, incentives and mental models typically found in philanthropic funders, acknowledging that this is shifting (as we explore further below). For example, traditionally philanthropic funders might value learned expertise over lived expertise, favour funding short-term ‘sticking plaster’ solutions by looking for quick fixes, lack diversity, and might use models that promote competition rather than collaboration. They also often exercise some form of power, not only in the resources they hold, but in setting the criteria, timescales, decision-making and monitoring processes of their grants and project proposals.

Barrow Cadbury Trust is an unusual funder by taking a long-term, systemic approach to shifting paradigms. One example is their longstanding support of the Transition to Adulthood Alliance. IVAR recently evaluated this approach to systems change, and we highlighted some of the important key themes and learning from that report:

| Collaboration and relationship-building | ‘The starting point for T2A is not a goal but a collaboration.’

‘The best agendas for systems change work are built from diverse perspectives – no one knows “the right answer” |

| Power dynamics

| ‘Funders need to make a conscious and sustained effort to shift the paradigm in their interactions with others – from oversight to partnership.’

‘Systems change efforts have too often neglected the expertise of people with lived experience of these systems. Supporting their leadership and agency is increasingly recognised as crucial to achieving meaningful change.’ |

| Long-term commitment

| ‘A long-term view can absorb the ups and downs and the capacity to build relationships.’

‘We’re not governed by performance indicators – things taking a long time doesn’t deter us.’ |

| Working with emergence and unpredictability

| ‘Complexity theory captures the reality that over time you will encounter both the expected and unexpected.’

‘Working in and with complexity requires a different mindset and a different approach: dynamic, adaptive, emergent.’ |

IVAR’s findings mirror Catalyst 2030’s open letter for NGOs to sign, calling for funders to take a more systemic approach to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. One of these goals, SDG 16, relates to peaceful and inclusive societies and justice for all.

IVAR drew attention to Barrow Cadbury’s mindset shift, seeing themselves primarily as a systems change partner, rather than a funder. The report found the distinction between ‘being a player, rather than just an enabler’ has been deliberate and intentional, as Barrow Cadbury Trust are proud to both ‘drive and serve.’ This activism is done in collaboration with alliance members and with a vital awareness of the need to ‘out the power dynamic by relational means; listening carefully, responding to challenge, showing respect, being flexible, deferring to greater expertise and building partnershiprelationships not administrative ones.’

We also discussed a report and system map by New Philanthropy Capital showing that advocacy activities aimed at influencing political systems get less than 2% of all money going to criminal justice-focused NGOs and system coordination activities get less than 1%. We also highlighted the findings of two other reports (by Harm 2 Healing and Rosa) which show that grassroots, ‘by and for’ organisations promoting racial and gender justice often miss out on funding due to bureaucracy, a lack of unrestricted funding to support capacity building and the instability and uncertainty of short-term funding.

Laurie highlighted an example of partnership working between funders, where Barrow Cadbury convened a group of philanthropic funders to collaboratively help tackle racial disparities in the criminal justice system and address important issues of capacity building and leadership development for ‘by and for’ organisations.

We used the Berkana Institute’s Two Loops model to demonstrate the transition from the current dominant paradigm (in this case, funders as funders) to the new emergent paradigm (in this case, funders as systems change partners). We wanted to identify some of the ‘seeds of change’ happening globally and to start connecting and illuminating them.

Attendees gave examples of where they had started to see shifts from the current dominant paradigm of ‘funder’ towards ‘systems change partner’. Some interesting examples from around the world were shared, including:

- Children’s Investment Fund Foundation—a global funder which takes a systems change approach by investing in the long term, focusing on root causes, having a high appetite for risk, being flexible, and investing in building a thriving ecosystem and emerging leaders.

- Viable Cities – a challenge-driven, strategic innovation programme in Sweden where people submit ideas as individual organisations and then collaborate with other applicants to design projects to create climate-neutral cities by 2030.

- NCVO – a voluntary sector infrastructure body in the UK which is exploring the use of collaborative funding applications.

It was clear that attendees wanted to see more of these shifts in the future. As the IVAR report found, trusts and foundations are uniquely placed to support systems change as ‘they have the money, the time, and the patience. They can afford to take risks, to shift power, to disrupt, to play a leading role, like Barrow Cadbury Trust, or to be a patient cheerleader. All of these choices are in their gift.’

We hope the workshop gave a small taste of how systems approaches and systemic funding can help tackle complex issues, including in the criminal justice sector. As one attendee concluded, working in these ways helps bring people from ‘systems blindness to systems sight’.

Nina Champion, Gemma Buckland, Nadine Smith and Laurie Hunte

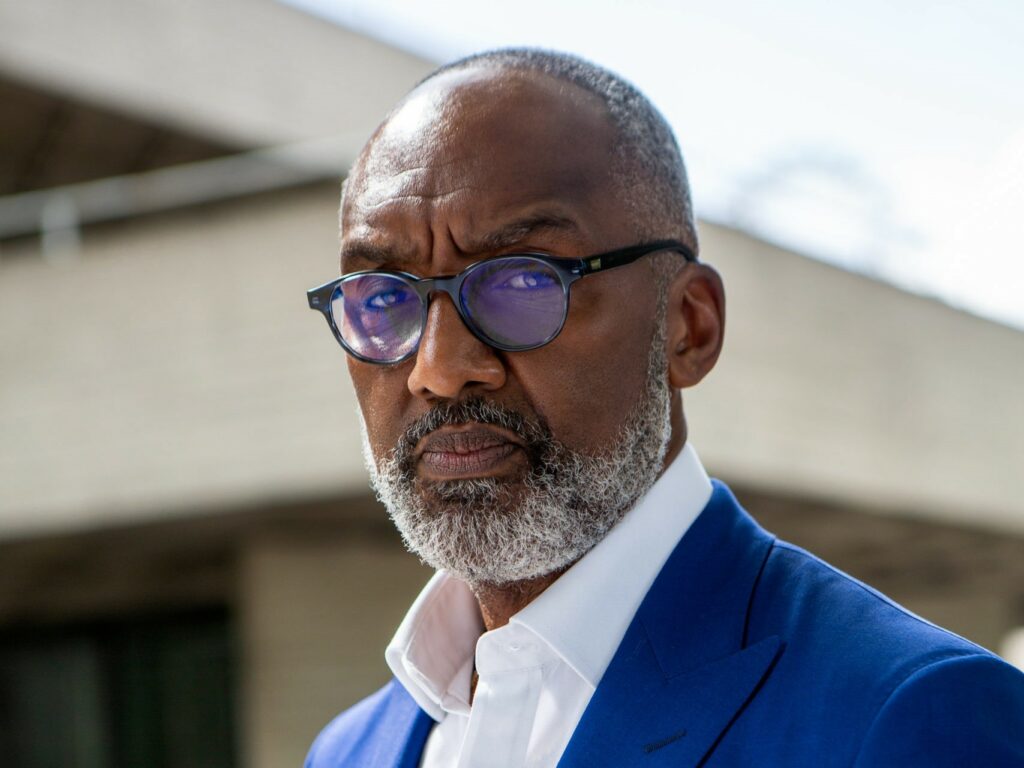

T2A Chair Leroy Logan MBE reflects on the findings of the Alliance for Youth Justice’s (AYJ) briefing paper on the transition from the youth to adult justice system – focusing on the experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people.

A spotlight on racial disparities

As the briefing suggests, young people who turn 18 while in contact with the justice system face a steep cliff edge. Studies show that this age is a crucial turning point where many young people begin to desist from crime with the right support and interventions. But rather than take advantage of this capacity for change, statutory services fall away. For Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people, the transition to the adult justice system can be even more challenging.

This latest briefing from AYJ has cast a harsh spotlight on the failings of our justice system to address the racial disparities that have blighted many young people’s lives. From an early age, many Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people find themselves associated with criminal stereotypes. Labelling young people in this way is incredibly damaging, eroding self-belief and making it harder to move towards a pro-social identity. Once Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic children enter the justice system, they are less likely to be diverted, more likely to receive harsher sentences, and more likely to be sent to custody, sentenced or on remand, compared to white children.

“Guilty before proven innocent… you kind of learn authority figures don’t actually care.” – (Young person)

This can create a huge gulf in understanding and trust between Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young adults and the professionals working in the system. Sadly, these findings confirm what many of us working in the sector already expected. That’s why I welcome AYJ drilling down into the causes of this crisis, and what needs to change to deliver better outcomes. Too often, we focus solely on what’s not working and forget that we must create a roadmap for the future we wish to see.

An over-stretched and under-resourced system

It’s clear that even with a diverse workforce, culturally competent training, and the best will in the world, the probation service is struggling to keep its head above water. A professional quoted in the briefing had this to say: “Record levels of staff sickness, extended sick leave, people fleeing the service in droves – that then exacerbates every other issue we have. We can’t be ambitious, we can’t be progressive, we can’t make many changes if you’re barely able to keep the regime running.” There are many admirable professionals working in the system who want to do better for young adults, but they don’t have the time, resources, or support to implement creative approaches. Without sufficient investment, the system can barely meet young adults’ basic needs – let alone support them to take steps towards a more positive future.

Collaboration with the VCSE sector

In this depressing climate, the work of voluntary and community organisations has become even more vital. Specialist Black and Ethnic Minority-led organisations have an intimate understanding of the communities Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic young people come from and how their experiences inform their behaviour and identity. As the research highlights, these grassroots organisations are well placed to provide nuanced support that recognises these young people’s overlapping needs – support that statutory services would struggle to provide.

These organisations are also more likely to have lived experience embedded in their staff and support services, meaning they can provide peer mentoring and positive role models – both of which are essential components in facilitating the shift towards a pro-social identity.

Ring-fenced funding to commission specialist organisations

I believe that we could take this further by developing a model where specialist Black and Minority-Ethnic led grassroots organisations are commissioned to operate services in their communities. Funding would be ring fenced for these local organisations who have the expertise to deliver the best outcomes. This model could be supported by local roundtables where information and knowledge are shared regularly so that young adults can access support from multiple agencies. Meeting in this way will also help criminal justice agencies better understand how these organisations are well placed to support young adults. Having buy in from all partners will be vital to the success of this model.

The Newham Transition to Adulthood Hub is a great example of how this approach can work in practice. They have a wide variety of services in one space, so staff can consult each other on individual cases and referrals to different services are much easier and more efficient. Regular spotlight sessions are held where different teams share their expertise and explain how their services can benefit young adults.

Grassroots organisations excluded from funding opportunities

Unfortunately, the AYJ’s report found that organisations with strong community links and knowledge are effectively excluded from funding opportunities. They lack the resources to compete with larger organisations who can meet the excessive commissioning processes and compliance requirements demanded by the Ministry of Justice and HMPPS. However, many of these larger organisations lack the knowledge and cultural competence to successfully deliver these services. Shockingly, they often sub-contract their services at a lower rate to the very grassroots organisations that have been denied a place at the table.

It is crucial that the Ministry of Justice and HMPPS immediately reform VCS funding allocation so that specialist Black and Minority-Ethnic led grassroots organisations can build the capacity of their services – ensuring every young person receives age-appropriate, trauma-informed, culturally competent services that reflect their entire lived experience.

This blog has been cross-posted with the kind permission of the Diversity Forum

The Diversity Forum is delighted to have secured additional funding from The Connect Fund for the co-creation of a data dashboard to reflect the diversity of the social investment sector. This project is being run in collaboration with our valued partners at For Business Sake, Clearview Research, Access – The Foundation for Social Investment, Big Society Capital, the Pathway Fund, Shift Design and Social Investment Business.

This project has been initiated in response to several requests seeking best practice for data collection around the diversity characteristics and a recognition of multiple intermediaries working on very similar goals. Our intention for the project is to improve the standards of data collection in the sector, setting expectations for best practice and facilitating a way to achieve this that is both accessible and inclusive by co-creating diversity data collection – in terms of content (what data is collected), process (how the data is collected), practice (how the data is used) and communication (how the data is visualised and shared).

We aim to do this by using a Design Thinking approach to centre individuals in social enterprises and social investment intermediaries, particularly those from marginalised backgrounds, to ensure a balance between accessibility and accountability and to ensure the data collected can be purposefully applied to improve goals around equity, diversity and inclusion. Our aims and intended outcomes for the project are as follows:

An accessible digital dashboard to portray the diversity of social intermediaries within the sector that can be updated on a regular basis

A baseline of good practice regarding appropriate questions for diversity characteristics for use within the sector

A user-led, co-created data collection method for the diversity of social investment intermediaries to regularly input diversity data that has the potential to be scaled for use with social enterprises

An evaluation report to indicate how this dashboard can feed into wider equity, diversity and inclusion work in the sector and practical recommendations for how our pilot can be scaled for wider use in future .

We are keen to engage with others working on diversity data collection to learn from your experiences and to integrate and collaborate our methods with as many others as possible across the sector. To get involved, ask questions or learn more about the project please reach out to us on [email protected].