Migration

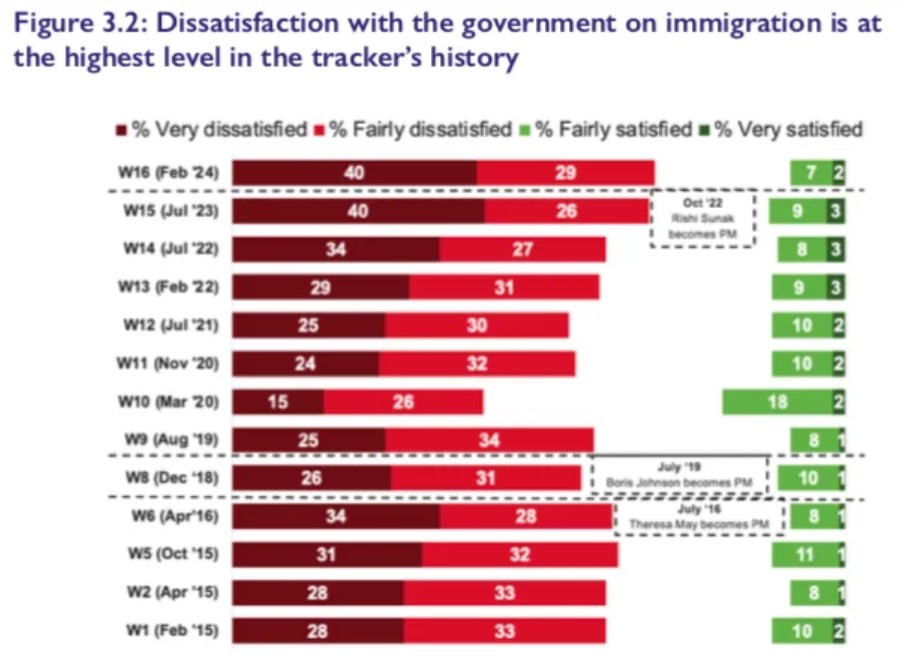

Public dissatisfaction with the Government’s handling of immigration is at its highest level since before the EU referendum, according to new data from the Immigration Attitudes Tracker from Ipsos and British Future, which has tracked public attitudes to immigration since 2015.

The findings are set out in a new report, Immigration and the election: Time to choose, published by British Future.

Some 69% of the public say they are dissatisfied with the way the current government is dealing with immigration and just 9% are satisfied. Only 16% of current Conservative supporters – and just 8% of those who voted Conservative in 2019 – are satisfied with the government’s handling of the issue.

Reasons for dissatisfaction vary according to people’s politics. The number one reason given is ‘not doing enough to stop channel crossings’, chosen by 54% of those who are dissatisfied, with 51% also saying it is because ‘immigration numbers are too high’. Yet 28% of those dissatisfied say it’s because of ‘creating a negative or fearful environment for migrants who live in Britain’ and for 25% the reason is ‘not treating asylum seekers well’.

For Labour supporters who are dissatisfied with the government, ‘Creating a negative or fearful environment for migrants’ (42%) is as important as ‘Not doing enough to stop channel crossings’ (41%).

Immigration and the election

When we do finally go to the polls later this year, will this be an ‘immigration election’ asks the report? Only for a minority. Around half of Conservatives (53%) say the issue is important in deciding how they will vote in the coming election, but it still comes after after the NHS (57%) and cost of living (55%) as their third most important issue. For Labour voters immigration ranks 12th in importance, with half as many saying it matters in deciding their vote (27%).

A numbers game?

In a period of high net migration, the new tracker survey finds that 52% of the public now supports reducing immigration (up from 48% in 2023). Four in ten people do not want reductions: 23% would prefer numbers to stay the same and 17% would like them to increase. Support for reducing immigration is still significantly lower than in 2015, the first year of the tracker, when 67% of the public backed reductions.

Attitudes differ significantly by politics. Seven in ten Conservative supporters (72%) want immigration numbers reduced. But most Labour supporters don’t, preferring immigration numbers to either remain the same (32%) or increase (20%), while 40% want reductions.

However, even those who want lower numbers find it difficult to identify what migration they would cut. Almost half of the 337,240 work visas granted in 2023 were ‘Skilled Worker – Health and Care’ visas. The tracker finds that 51% of the public would like the number of doctors coming to the UK from overseas to increase (24% remain the same, 15% decrease); 52% would like the number of migrant nurses to increase (23% remain the same, 15% decrease) and 42% would like more people coming to the UK from overseas to work in care homes (27% remain the same, 18% decrease).

For a range of other working roles, support for not reducing immigration numbers is higher than that for reducing them. Less than 3 in 10 people support reducing numbers of seasonal fruit and vegetable pickers, construction labourers, restaurant & catering staff, teachers, academics, computer experts and lorry drivers coming to the UK. When allocating work visas for immigration, the public would prefer the government to prioritise migration to address shortages at all skill levels (52%) than attracting people for highly skilled roles (26%).

Support for reducing the number of international students coming to the UK has increased by 4 points, with around a third of people (35%) preferring numbers to be reduced. But most of the public (53%) does not want to reduce student numbers. A third would prefer numbers to remain the same (34%) and a further fifth (19%) would like to see them increase.

The politics of immigration

As the UK heads towards a General Election, the tracker finds that the Labour Party is more trusted than the Conservatives to have ‘the right immigration policies overall’. Reform UK is slightly more trusted than the Conservatives but less trusted than Labour. Some 22% of the public says they trust the Conservative Party to have ‘the right immigration policies overall’, while 68% say they don’t trust the party. For Labour, 33% trust the party while 51% say they don’t. And 26% of the public says they trust the Reform UK Party on immigration, while 47% say they don’t – a similar score to the Lib Dems (trust 23%, distrust 50%).

Among leading politicians tested, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak had the highest ‘distrust’ score, with 70% of the public saying they do not trust the PM on immigration and 21% saying they do. Some 57% say they distrust Labour leader Keir Starmer on immigration, with 31% saying they trust him. Nigel Farage is distrusted by 59% of the public on immigration and trusted by 29% – making him slightly more trusted than former Home Secretary Suella Braverman, who is distrusted by 63% and trusted by 22% of the public.

Refugees, asylum and Rwanda

On asylum, the tracker finds that 47% of the public supports the Rwanda scheme and 29% are opposed to it. Opinion is divided by politics, with 75% support among Conservatives (and 10% opposition) compared to 31% support among Labour supporters and 47% opposition.

Only 32% of the public thinks the Rwanda scheme is likely to reduce the number of people trying to enter the UK without permission to seek asylum, while 56% think it is unlikely to do so.

Because the Rwanda scheme has often been mis-described, for instance as an offshoring scheme, the tracker tested which of three versions of the Rwanda policy people prefer:

- 32% chose the description of the government’s actual Rwanda scheme: “Remove asylum seekers to Rwanda to claim asylum there, without first assessing the claim.”

- 25% preferred a different version of the Rwanda scheme to the one that the government is pursuing: “Assess these asylum claims in the UK first, to only consider removals to Rwanda for those whose asylum claims fail”.

- 26% chose “Do not send anyone to Rwanda, regardless of how they arrived.”

- 5% chose “none of these” and 12% “don’t know”.

Overall, more people still think immigration has a positive impact on Britain (40%) than a negative impact (35%) though positivity has fallen slightly, by 3 points, since the last tracker in 2023 and from its March 2020 peak of 48%.

Ipsos interviewed a representative sample of 3,000 adults online aged 18+ across Great Britain between 17-28 February 2024. Data are weighted to reflect the population profile. All polls are subject to a range of potential sources of error.

This Migration Observatory briefing examines the UK’s ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’ (NRPF) condition, which applies to people on temporary immigration statuses, and prevents access – in most cases – to state-funded welfare. It examines the likely number of migrants that have the NRPF condition attached to their immigration status and their characteristics, including how many are at risk of destitution.

Key points:

- At the end of 2022, about 2.6 million people held visas that typically have NRPF, substantially up from previous years.

- At the end of 2022, the top nationalities in visa categories with NRPF were India (665,000), China (316,000), Nigeria (268,000), Pakistan (147,000) and Hong Kong (121,000).

- EU citizens who moved to the UK after 31 December 2020 under the new immigration system (84,000 at the end of 2022) have NRPF attached to their status.

- All residents with irregular immigration statuses are subject to the NRPF condition. There are no official statistics about the size of this group, which is estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands.

- Among recently arrived migrants – the group most likely to have NRPF – just under 100,000 live in economically vulnerable households (where all working-age adults are inactive, unemployed, or in low or low-medium skilled jobs) with dependent children.

- Recently arrived migrants from Bangladesh (27%), Pakistan (21%), and Iran (18%) have the highest likelihood of living in a deprived household.

- An estimated 10% of non-EU citizens with less than five years of residence receive public benefits (which is allowed e.g. if they are a refugee or are in a family with a UK citizen or person with recourse to public funds), compared to 25% of UK nationals.

- There were 2,500 successful applications to lift the NRPF condition per year in 2021 and 2022, which is comparable to pre-Covid years.

Find out more about NRPF and download the briefing.

This new report from Migration Exchange (MEX) presents a comprehensive review of the UK refugee and migration sector and independent funding landscape, looking at areas of growth and focus since 2020, with insights on key thematic areas.The sector in 2023 – key stats

Analysis of Charity Commission data and survey results revealed interesting findings on the size, focus and resources of the sector, including:

- The refugee and migration sector includes registered charities, other formally constituted not-for-profit organisations, a wide range of voluntary and community-based organisations, and international organisations.

- There has been an increase of 137 new charities (24%) established between 2020 to 2022 which work on refugee and migration issues.

- Funding to the sector increased significantly (51%) between 2020 and 2022 – largely due to emergency funding in response to Covid-19. However there are concerns about whether this funding level can and will be sustained.

- Resources to the sector are heavily concentrated in large organisations. In fact just 3% of charities in the core sector control 44% of the funding.

- NGOs remain largely dependent on trusts and foundations for funding.

The sector in 2023 – key priorities

Drawing from interviews and consultation workshops, the report presents deeper analysis and suggested actions around six key priority areas:

Adapting to external challenges and crises

Funding for more systematic and strategic collaboration, including horizon scanning, shared funding infrastructure and legal advice, can strengthen our power to go beyond rapid response.

Financial sustainability and funding

By investing more in those doing ground-breaking work where the need is great, independent funders could spread their support more equally. A shared approach to growing the overall funding pot would also help build a solid foundation for the future.

Racial justice, power and lived experience

Real change will only happen when those with power reflect deeply on the lasting impact of colonialism and racial injustice, and start distributing resources differently. Additionally, involving people with lived experience of migration is a vital step towards achieving fundamental, inclusive and collective change.

Employee wellbeing and leadership

By urgently investing in collective care, leadership development, and fair work and pay policies, people will feel safe and protected.

Influencing and campaigning

To prepare for the 2024 General Election, we can benefit from building wider alliances that link frontline expertise with political influence and power.

Alliances and collaboration

Solidarity with people on the move is the bond that connects organisations across our sector. But we need more time and new opportunities to deepen collaborations and broaden our alliances. By pooling our power and expertise we can present a united front on the issues that matter most, and create a better future for everyone.

Which industries can bring in migrant workers – and which cannot – will be one of the defining questions in migration policy if the UK Government ends free movement after Brexit, according to a new report from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. The new report, Labour Immigration After Brexit: Trade-offs and Questions about Policy Design, considers the options for post-Brexit labour immigration policy and their potential ramifications.

The report notes that reducing EU migration after Brexit is a key government objective. However, deciding how and where to achieve such reductions is not a simple statistical exercise but involves a series of subjective, political decisions. Some industries and businesses will see bigger impacts than others, and deciding which ones should be allowed to bring in migrant workers could be a contentious process.

Perhaps the single biggest question about migration policy after Brexit is how much—if any—of the demand for low- and middle-skilled workers the Government will satisfy, the report argues. The Government has indicated that high-skilled EU workers are not likely to be the main target of measures to reduce migration after Brexit.

The report notes that the Government faces a choice between implementing a tailored migration system which is responsive to differing policy goals (such as supporting specific industries like agriculture or reducing the cost of social care) and a simpler set of rules that can be applied more uniformly across all industries. There are pros and cons to each approach: a tailored system enables the government to put immigration policy at the service of other government objectives like industrial strategy or supporting public services, but is also more complex and harder to implement.

Madeleine Sumption, Director of the Migration Observatory and author of the report, said: “There’s no single, objective metric to decide which industries should continue to receive new migrant workers after Brexit. The Government will need to juggle several different objectives, like the desire to reduce migration, support particular sectors, or to negotiate a new relationship with the European Union. Some of these objectives will inevitably conflict, so the challenge will be deciding how to prioritise them. Ultimately, a fair amount of political judgment will be needed.”

The following article is one of several pieces which are part of Policy Network’s ongoing project on immigration and integration supported by the Barrow Cadbury Fund.

In four weeks’ time, amid the pageantry of ceremonial Washington, the 45th president of the United States will be sworn into office. A man who won that office on, among many other horrors, a promise to ‘ban’ (albeit temporarily) Muslims from entering the US.

He may be rolling back on that offensive policy now the Oval Office looms in vision, but the point is telling. Fear of Islam remains real and potent across the west, even a decade and a half on from 9/11.

In Europe the ‘refugee crisis’ and a series of terror attacks over the past two years have flared tensions. Last night’s appalling incident in Berlin has already sparked a torrent of racist remarks on social media, following early reports that the driver may have been from Pakistan. It seems almost inevitable that public discourse will soon return to the sensitive topic of whether Islam is compatible with ‘western’ values.

In recent weeks Chancellor Merkel has joined the chorus of politicians floating support for a burqa ban, showing it is not just ‘populists’ focusing on the issue.

This week Policy Network’s contributors seek to go beyond simplistic rhetoric and policies, concluding it’s time to rethink the way we use terms such as ethnicity, identity, culture and race. Our contributors probe the integration debate – focusing on cases in Britain, France and Germany – to consider the effectiveness of different responses to public concern. These range from policymaking to acts of symbolism and how politicians choose to react to fear.

These pieces are part of our ongoing project on immigration and integration supported by the Barrow Cadbury Fund and follow a successful recent seminar in London: ‘Inclusive integration: how can progressives promote social cohesion in divisive times?’, the audio of which is now available.

Barrow Cadbury Trust’s CEO Sara Llewellin was asked recently by New Philanthropy Capital to speak on a conference panel about how she thought charities could help heal divisions in society. Below is an edited blog of her presentation.

It is impossible to do justice to a post-referendum analysis or to go beyond the ‘known knowns’ in a short piece, but for the purpose of this blog there are several key features we need to think about when developing a strategic approach to the coming several years. The bloody nose given to the political establishment needs attention. Firstly, although the salient political hook for the Leave Campaign was migration, this was in reality a proxy for being ‘left behind’ by globalisation. People were sick and tired of being told they benefited from migration when they knew very well that they didn’t or didn’t much. Most of us who lead charities do and that leads us straight into the heart of a paradox. We want to heal the very thing we are part of creating. Or put another way we want to ‘fix’ what’s wrong with other people. Put like that it sounds pretty top down.

Secondly, it’s not as simple a binary as it first appears. Lots of the prosperous south voted Leave, Liverpool voted Remain and let’s not even start to unpick the four countries question! 52%/48% is half and half more or less and the voting patterns show not whole areas of the countr(ies) voting one way but most areas voting relatively evenly. So the divisions are not between places but within them. Even within families. Not to say there is no North/South issue, of course there is. But as charities we are going to have to think much harder about how to be effective, for example, in place based work and what funders sometimes call ‘cold spots’.

Thirdly, and from a practical point of view very importantly for our sector, many of the EU funding streams such as the European Social Fund map right onto the strongest Leave areas. What are the implications of that for the work of our social sector? I suggest bravery in refocusing should be on our agenda.

Immediately after the referendum we saw a spike in xenophobic and race hate crime. The good news is that shortly before the referendum British Future polling showed that 67% of eligible voters thought that EU citizens already in the UK should be given permanent leave to remain in the event of a ‘leave’ vote. Shortly after the Referendum in repeat polling we saw that figure go up slightly. So we can deduce that the majority of Leavers do not endorse this kind of behaviour. But we were perhaps complacent too soon. Yes, the spike has abated but not returned to previous levels.

So the community sector should certainly have a role in ‘holding the line’ in a context where some people now feel they have a licence to abuse. And we have to walk to the bit of a tightrope where we recognise people’s concerns, recognise they are not born of racism but also draw a line at what we might call ‘decency’. There is a threshold beyond which it’s not okay to go. Remainers and Leavers both.

Over the past eight years or so, we and several other foundations have been working together on public attitudes to migration, integration and British identity. We set up British Future, a new organisation working solely on the issue of opening up dialogue and trying to build a narrative aimed at the ‘persuadable and anxious middle’. We now have a considerable body of evidence which suggests that about a quarter of British society is actively hostile to migration and about a quarter actively supportive of it. That half of the population is unlikely to change their views. The other half are what are called the ‘anxious’ or ‘persuadable’ middle. About half of those are economic sceptics – typically blue collar workers who are worried about job security, their children’s futures, wage stagnation and access to housing and public services. The other half are cultural sceptics, worried that ‘this doesn’t feel like my country any more’ or ‘when I get on the bus I cannot hear any English spoken’. Opening a dialogue with these two groups needs differentiated approaches. And what we have found, among many other things, is that listening is more important than lecturing. If you give people a diet of facts and evidence, it is not only ineffective, it is counter-productive. We need much more of this more open dialogue because migration isn’t going away any time soon.

What makes people feel powerful, autonomous, in control? This is a key question for our sector because the Leave Campaign’s greatest success was the slogan ‘Take back control’. What are we going to offer people so that they feel they are getting that? The only possible answer to that is ‘bottom up’ not ‘top down’ – communities organising and delivering their own visions. There’s a lot of noise in our sector about enabling voice but it is a difficult thing to do well and is often more neglected than pursued. And we would do well to hear in mind the disability movement slogan ‘Nothing about us without us’.

A lot of the best work welcoming newcomers has come from the faith communities and we would be wise to build on that. In fact we would be wise to build on existing infrastructure in general because new initiatives take years to mature. So we should be seeking and brokering alliances at the local level, while at the same time promoting good bridge building work on a national scale. Last year we and others convened a meeting of funders to listen to key leaders in the migration sector about the refugee emergency. What they told us was that the unprecedented outpouring of good will in this country would waste, evaporate and even sour if not harnessed. So we set up a new, pooled fund for refugee and migrant welcoming work at the very local level. It is managed for us by the UK Community Fund and so far is going very well. Its focus is on the welcome given rather than the welcome received.

I have been convening and chairing a series of meetings with foundations in the UK and in Europe on the implications of the Brexit vote. Some of the practical things to emerge are concerns about European Social Fund for example. One of my reflections on that is – who is going to lobby for poorer people and communities when it comes to divvying up the UK cake? The universities, the farmers and the scientific communities are all working their socks off on this already and have capacity to act. I suggest this is one of our own sector’s responsibilities.

And finally, a word or two about putting our own houses in order, or as the young people would say, checking our privilege. Much of the charity sector still reflects our patrician roots. Certainly the charities of any size are suffering declining public trust such that we are less trusted now than the supermarkets. I think that illustrates that we are part of the problem unless we consciously, deliberately and purposefully make it otherwise. So for me part of what the Leave vote told me was to increase transparency and accountability and to beware of parachuting into other peoples’ realities without consulting them.

Of course there is good, solid community-building work in lots and lots of places. But it is not unusual for different communities to be building their own social capital in parallel universes. Where in the past we have thought of that in terms of race and ethnicity, particularly in some of the northern cities, should we now be turning our attention to broader bridge building and shared endeavours? The Sustainable Development Goals do now offer a framework for this and I urge you all to take a good and considered look at them. With the strapline ‘leave no one behind’ the major change from the Millenium Development Goals is an insistence that these goals are not only about the global south, they are about all people everywhere. We have to start decreasing the gap in equalities in every place, not just between richer and poorer nations, if we are to heal the divisions which have been so sharply revealed.

A new report from the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford ‘A Decade of Immigration in the British Press‘ says that over the past 10 years British national newspapers moved away from focussing on illegal immigration and instead focused on the scale of legal immigration, EU migration and the need for “control”.

The report also highlights the role that journalists and media organisations have played since 2006 in framing narratives about migration. Nearly half of all stories analysed in detail relied on statements or arguments made by the journalist, rather than reporting of the views of external sources such as policy-makers, NGOs, community organisations or academia.

Key findings from the report include:

- A sharp increase in newspaper migration coverage over the course of the Conservative-led coalition government from 2010.

- An apparent change in how immigration is discussed, with a significant decline in discussion of the legal status of migrants and an increase in the focus on the scale of migration from 2009 onwards.

- A rise in the relative importance of discussion relating to ‘limiting’ or ‘controlling’ migration since 2010.

- A sharp increase in the frequency of discussion of migrants from the EU/Europe after 2013, with a particular spike in 2014 when migrants from Romania and Bulgaria achieved full access to the UK labour market.

- A tendency for journalists themselves to play the role of framing problems in the migration debate, rather than simply reporting on others’ (such as politicians’ or think-tanks’) analysis.

- A tendency to hold politicians responsible for problems relating to EU migration, while migrants themselves are more likely to be held responsible for problems relating to illegal migration.

Newspapers included in the analysis were: Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror; Daily Star and Daily Star Sunday; The People; The Sun; Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday; The Express and Sunday Express; The Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph; the Financial Times; The Guardian and The Observer; The Independent and the Independent on Sunday; The Times and Sunday Times.

The News of the World and The I newspaper were not included in the analysis because they were not published continuously throughout the study period, leading to problems with data collection.

About the Migration Observatory

Based at the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS) at the University of Oxford, the Migration Observatory provides independent, authoritative, evidence-based analysis of data on migration and migrants in the UK, to inform media, public and policy debates, and to generate high quality research on international migration and public policy issues. The Observatory’s analysis involves experts from a wide range of disciplines and departments at the University of Oxford.

In a new report released today, Britain’s immigration offer to Europe, British Future sets out a proposal for a new, preferential system for EU immigration to the UK. Such a system, it argues, could secure UK public support for immigration in a managed system which is fair to migrants and host communities; yet remains politically deliverable in Westminster and for the EU and its member states too. According to the report many think immigration presents an impossible conundrum for the Brexit negotiations. But could we find a system that helps rebuild trust while continuing to welcome European migration to Britain and, crucially, gives UK negotiators a positive offer to make to the EU as it seeks the best possible trade deal?

The British Future proposal offers preferential European access to the UK labour market as part of a UK deal on trade with the EU. It retains freedom of movement for EU workers above a set skills or salary level: UK attitudes research shows that 88% of the public does not want to reduce the migration of skilled workers that our economy needs. They would, however, like greater control of low- and semi-skilled immigration, which would be subject to quotas, set annually by Parliament, after consultation with employers and local communities. Importantly, the first opportunity to fill those low-skilled migrant quotas would go to Britain’s preferential trade partners – and the first offer of such a preferential trade and migration deal should be made to the EU.

It is essential that migrant workers are treated fairly and offered routes to settlement and citizenship and we make clear that this is not a guest worker system. We believe this is a constructive offer that is capable of securing support from within the European Union. What’s more, it could help to rebuild public trust in our immigration system here in the UK. A preferential system would bring unskilled migration under UK control, while still ensuring that employers can recruit the staff they need to keep our economy growing, and our country remains open to the immigration that we want and need.

Migrants and refugees cross borders to live among us for many reasons. Some come fleeing human rights abuses. Some come to join other members of their families. Some come to take up work or study. But when they arrive here they often find that they face new challenges and problems. Some not only rise to these challenges for themselves, they also help others to succeed. The Women on the Move Awards celebrate and promote the contribution that migrant and refugee women, the media and their champions can make towards facing down prejudice and inspiring others.

This year there are four categories of awards. The Woman of the Year and Young Woman of the Year awards celebrate women who, having migrated or fled persecution, provide essential support and inspiring leadership at a grassroots level to others starting a new life in the UK.

The Sue lloyd-Roberts Media Award recognises the outstanding work of a journalist or producer whose reporting has promoted the protection needs of migrant and refugee women. The Champion Award will also be presented to those who work to protect or promote the rights and/or integration needs of UK-based migrant and refugee women.

Find out about previous year’s winners 2012 ,2013 ,2014, 2015 2016.

If you know a woman who deserves to be recognised, nominate her below.

For more information please contact [email protected].

The New Beginnings Fund was set up by a group of funders, including Barrow Cadbury Trust, to provide support to organisations involved with welcoming and integrating refugees into the UK. Phase 1 of the Fund completed earlier this year. Find out about some of the initiatives funded under Phase 1. The applications for phase 2 of the New Beginnings Fund are now open. The deadline for submitting an expression of interest form is 30 October 2016. Please note, that web page will direct you to the relevant Community Foundation website.

For this phase grants will only be awarded in Yorkshire, the East Midlands, the North East, the South West, the South East, the East of England and Cumbria, Staffordshire, Manchester and Cheshire.

The New Beginnings Fund was set up to support small groups. Applicants must meet certain conditions before being awarded a grant. Find out more about the eligibility criteria. Read the Documents and Policies checklist before you submit an expression of interest.

Questions in the expression of interest form and application form