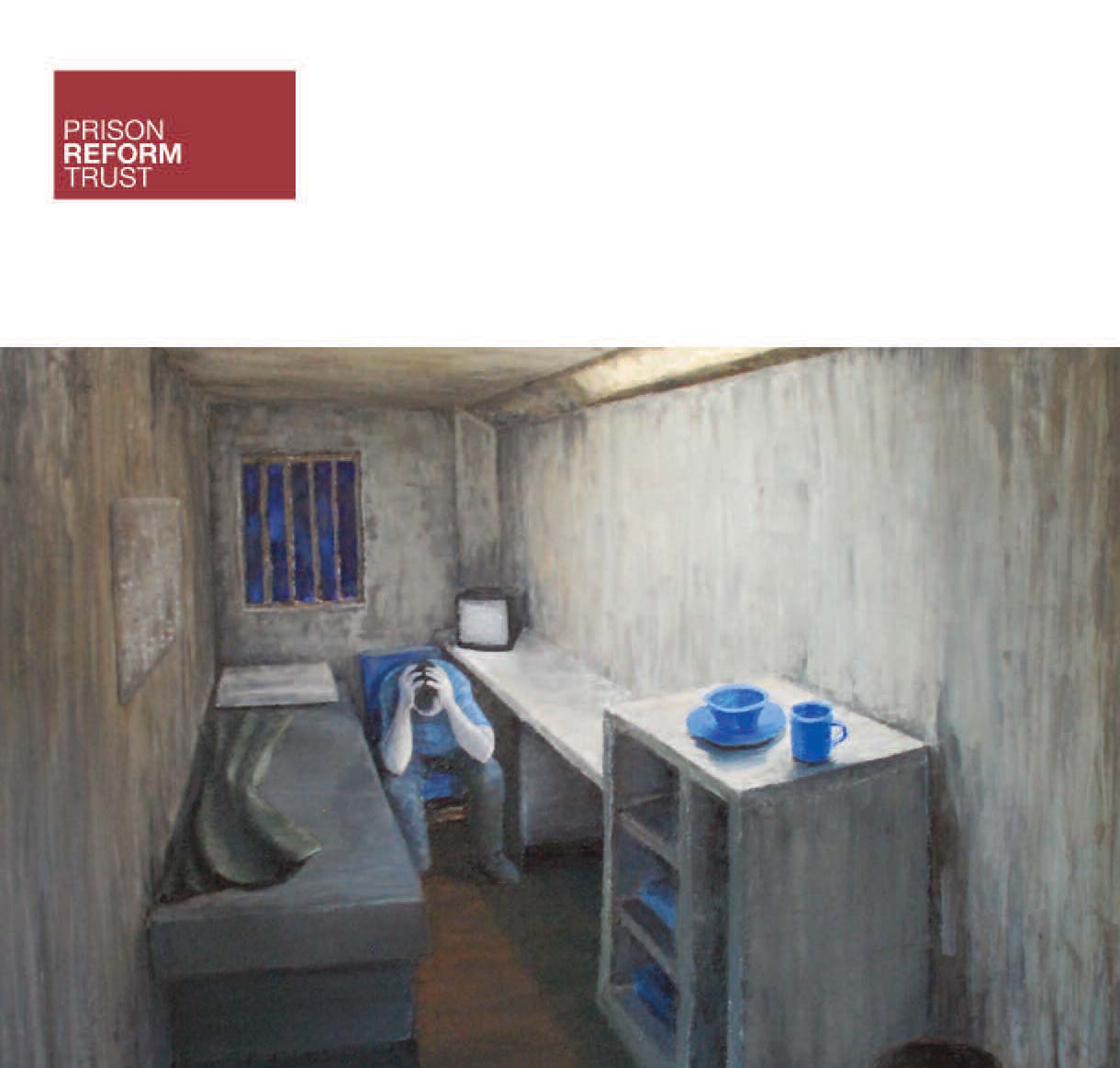

According to a new Prison Reform Trust report Deep Custody: Segregation Units and Close Supervision Centres in England and Wales ,supported by Barrow Cadbury Trust, people held in segregation in prisons experience impoverished regimes with poor levels of purposeful activity. The report says that more than half suffer from three or more mental health problems and finds that segregation units and close supervision centres (CSCs) perpetuate social isolation, inactivity, and increased control of prisoners – a combination proven to harm mental health and wellbeing.

Worryingly, over one-third (19) of the 50 prisoners interviewed who were held in segregation units had deliberately engineered a move into segregation to escape violence and indiscipline on prison wings or to raise concerns regarding their treatment and conditions. This, the report says, is an “important barometer of conditions on normal location” and the Prison Service “should target efforts to improve treatment of all prisoners accordingly.”

This independent research was facilitated by the Prison Service and is based on a survey sent to all prisons in England and Wales and visits to 15 prisons and interviews with 67 prisoners (50 in segregation and 17 in closed supervision centres (CSCs)), 49 officers and 25 managers. The report was written by international expert Dr Sharon Shalev of the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford and Dr Kimmett Edgar of the Prison Reform Trust.

Writing in the Foreword to the report, Lord Woolf, Chair of the Prison Reform Trust and a former Lord Chief Justice, said:

“The complexity of segregation brings many challenges to already beleaguered prison staff and prisoners who for whatever reason, cannot manage or be managed in, the main body of an establishment. Segregation, though it may sometimes be necessary, must not be prolonged or indefinite.

“Care must be taken to avoid, as far as is possible, the damage to mental health that exclusion will bring. Equally, care should be taken to avoid the use of segregation as a holding operation for people who should be transferred swiftly and humanely to a secure hospital or psychiatric unit.”

“I read with concern of those prisoners who were seeking the separation and withdrawal represented by segregation as a means to escape from violence and indiscipline on general location in some establishments.”

The report found that segregation units and close supervision centres are complex places, where some of the prison’s most challenging individuals are confined alongside some of its most vulnerable people, within a small, enclosed space. Almost one in 10 of the prison population spent at least one night in segregation in the first three months of 2014.

In January 2015, the total segregation capacity in England and Wales was 1,586 cells. Close supervision centres had a capacity of 54. Of those segregated, 71% spent less than 14 days in segregation, 20% spent between 14 and 42 days, and 9% were segregated for longer than 84 days. The average stay in CSCs was 40 months.

Over half of the prisoners interviewed for the study reported three or more mental health problems including anxiety, depression, anger, difficulty in concentrating, insomnia, and an increased risk of self-harm. Almost half of the officers interviewed said that they would benefit from more mental health training and that further training should be offered.

Good prisoner-staff relationships were a key strength of many segregation units with most prisoners saying that relations with officers are good. The authors witnessed examples of good practice, suggesting that the pressures placed on segregation units and CSCs need not result in a lack of decent treatment.

However, regimes in units were impoverished, comprising little more than a short period of exercise, a shower, a phone call, and meals. In most units, periods of exercise lasted 20-30 minutes, well short of the 60 minutes stated in the European Prison Rules and the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Mandela Rules). “Segregation must not be prolonged or indefinite”, said the authors. “More purposeful activities should be offered and exit strategies improved”.

Other findings include:

- Of the 17 prisoners held on CSCs, about half did not agree with or understand the reasons for their selection. A majority did not know what they needed to do to progress, and felt that opportunities to demonstrate a reduction in risk were limited.

- Only nine of the 67 prisoners interviewed felt that the Independent Monitoring Board (IMB) had helped them. Two-thirds were clear that the IMB, whose members are appointed by the Secretary of State for Justice, had not been helpful.